From Herders to Hikers, the Shifting Lives of Scottish Bothies

When I was 20 years old, I heard about huts in northern England and Scotland called bothies. I didn’t even know how to pronounce the name, let alone how to find them. Bothies are commonly described as open huts in remote places of Scotland, Wales, and England that remain unlocked and open to anyone. I soaked up all the information I could find, and a year later I found myself at the end of winter in a Scottish bothy called Invermallie.

“Bothying” is about simple human adventure. The huts’ small size and lack of privacy enforce a certain savoir-vivre. Their simplicity teaches us to know what is essential.

In freezing temperatures and surrounded by sleet, I reached the hut. Since bothies are by nature open to anyone, you never know who, and even if, you will meet anyone. But I was lucky. The smoke coming out of the chimney signaled to me that someone was there. When I stepped inside, I was met by Seth, an American with a huge beard, and Old Joke, the Maintenance Organizer in charge of the surrounding bothies.

Old Joke was a character. He was a patriotic Scotsman, but very warm and welcoming to the American and German strangers. He knew the hut inside out and used this knowledge to his advantage. He always had a bottle of whisky hidden for unexpected occasions like this one. “If anyone finds the whiskey, he deserves it because it’s bloody well-hidden,” he mumbled in a thick Scottish accent. So, we sampled a wee dram or two while sharing life stories. The stories were interrupted only when Old Joke started playing his guitar and singing traditional Scottish folk songs. The songs were mostly about the First World War and the Scottish national identity; topics that once divided nations, but in this instance connected all three of us.

“Bothying” is about simple human adventure. The huts’ small size and lack of privacy (you rarely find toilets) enforce a certain savoir-vivre. Their simplicity teaches us to know what is essential. Going back to the basics made me realize that we don’t need much to be happy. When spending time in these remote places, you need to be flexible. You need to be ready for a lonely cold night or a night spent in front of a warm fireplace with a group of wilderness lovers or pugnacious drunk men.

These havens of comfort and warmth follow five simple rules that organize this simple life: respect other users, the bothy, the surroundings, the Estate, and the restriction on numbers. Anyone who respects this Bothy Code is welcome to stay. These five principles show that it is indeed not only a human adventure, but a human-environment endeavor that is based on mutual respect.

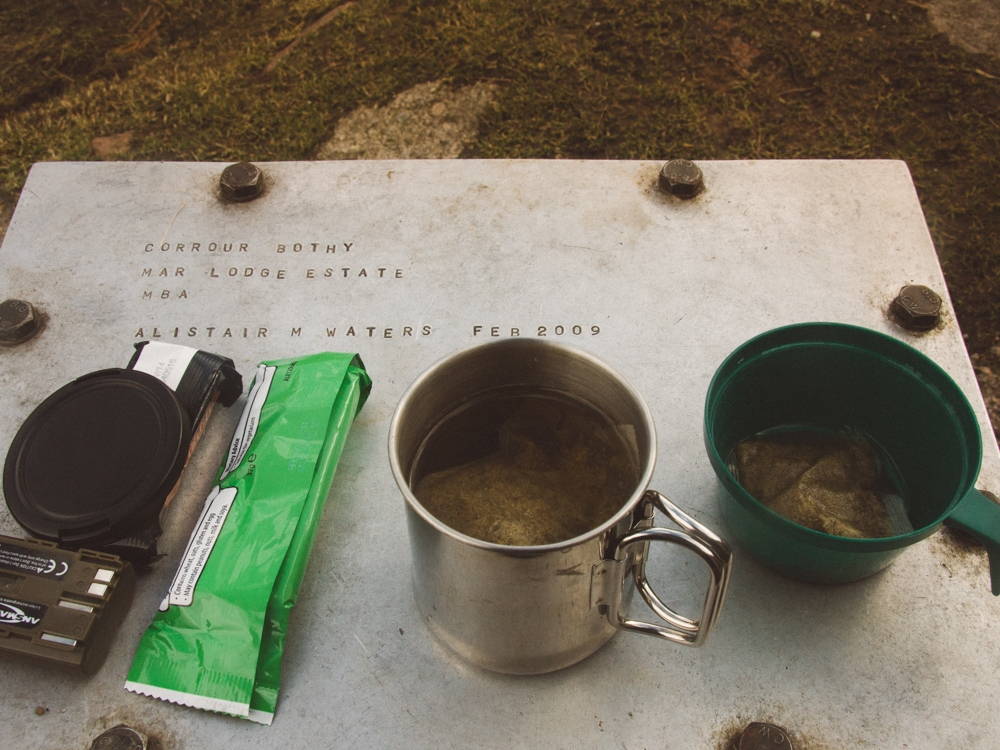

The shared supplies at the bothy at Dibidil. Photograph by Jonas Stuck, 2014. See below for a full gallery.

It is hard to imagine what these places were like before they were slowly transformed into bothies. Bothying in the recreational sense is a modern tradition dating back only to the Second World War. Nowadays they are mainly used by hikers, hunters, and climbers who are looking for an upgrade to their tents. It is easy to forget that these settlements were once home to whole families and their livestock. Since the 1920s, Scottish hill farming has steadily declined, leaving abandoned farmsteads. The growing economy increased average wages, shortened working hours, and saw mountaineering and hill walking become popular forms of recreation.

Development accelerated in the post-war era when Land Rovers allowed people and machinery to be easily transported to remote locations. Estates were now able to cut down their staff and centralize their housing to achieve better living conditions than they could expect in the hills. Struck by depopulation, the abandoned farms began to rot away. Walkers and cyclists started to use the deserted farms for overnight accommodation, sometimes secretly, but increasingly with the owners’ knowledge. Thus, ‘bothying’ was born.

During the 1960s, the number of walkers increased while the condition of many bothies deteriorated. Climbing clubs started to maintain a few bothies, but the rest received only random attention. This changed in the next decade when the Mountain Bothies Association (MBA) was formed, a charity that institutionalized “bothying.” The growth of the charity meant changes. Each individual bothy got its own nominated person, the Maintenance Organizer or MO, to look after the bothy. This professionalization led to an increasing number of bothies. During its more-than-fifty years of existence, the MBA has looked after a total of 123 bothies. Unfortunately, a few have been lost, but the number maintained has remained around 100.

Mindful of the code, we not only drank whisky with Old Joke, we also dedicated our next two days to repairing the hut. Old Joke brought a huge bag of cement and an arsenal of tools with him. The mission was to do some necessary repairs in and around the hut. We rebuilt a bridge across a small creek that was swept away by bad weather. This is what the bothy experience is all about: sharing thoughts and songs with strangers that become friends, but also emotionally investing time and energy to maintain the space that lets you connect with nature. Even though you don’t own the place, working on something that doesn’t belong to you will bring a certain amount of spiritual ownership, an emotional ownership that extends not only to the structure of the hut but also to the environment surrounding it.

Photography is my tool for capturing moments in the life of these spaces.

Click images below to enlarge. All photographs by Jonas Stuck.

Featured image: Glensulaig, 2016.

Jonas Stuck is a PhD student at the Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society in Munich. He studied contemporary history and political science in Lyon, Berlin, and London. In 2017, he joined the research group “Hazardous Travels: Ghost Acres and the Global Waste Economy.” His PhD research project, “Toxic Divide,” investigates the toxic waste trade between the two Germanys during and after the Cold War. Stuck’s photographs were first featured on Edge Effects as the first place winner in the 2018 “Working at the Edge” Photo Contest. Contact. Website. Twitter. Instagram.

Wonderful blog post!! I really love how you describe your experiences and your writing style. Great job!

Very nice story and awesome description!

I needed a break from work today and sat down to read this piece. Lovely.