Caring, at a Distance

As the world reels from the coronavirus pandemic and the global case numbers climb with terrible speed, I’ve been thinking a lot about trees. And loneliness. And what it means to care for one another when the experts insist the very best thing to do is to keep ourselves apart—to practice social distancing, to avoid non-essential contact, to “shelter in place.”

Trees already know how to protect one another with distance. In a phenomenon called “crown shyness,” each tree in a forest reaches up to the sun and yet each keeps its leaves to itself, just in case hungry leaf-eating larvae or disease might try to hitch a ride to its neighbors in the canopy. The gaps between them let in the light. It’s a beautiful thing, this careful distance.

Even still, distance doesn’t mean isolation. The forest survives in underground intimacies where trees share messages, nourishment, and warnings through dense fungal networks that span miles beneath the surface. They sustain themselves by sustaining those around them.

Lately, I’ve been thinking a lot about how trees manage entanglement and separation. And about what I owe myself, my loved ones, and a world of intimate strangers whose canopy I share. I began collecting books for this recommendation list weeks ago to honor women writers I admire during Women’s History Month. Today, I’m grateful for how these writers have entered my underground network as I shelter in place—messengers of care and hope in anxious and uncertain times. If you’re looking for ways to connect during quarantine, I hope they’ll offer something similar to you.

Finding Connection During Social Distancing

Inés Estrada, Alienation (Fantagraphics, 2019)

It’s 2054: fossils fuels are gone, wildlife is extinct, extreme weather and climate disasters are everyday occurrences, and human life struggles on in the few habitable cities run by corporate monopolies. Despite the comic’s post-apocalyptic setting, Estrada’s world is anything but dystopic. Alienation pulses with playfulness and hope as the novella’s two protagonists—Elizabeth (an erotic dancer who works exclusively over the internet and hasn’t stepped outside for years) and Carlos (who just lost his job on the last oil rig)—find new ways to combat isolation, boredom, and the overwhelming fear of poverty under authoritarian capitalism by connecting online. Drawn in pencil and published in blue ink, Alienation is a wild ride through lush virtual reality landscapes, encounters with extinct animals, Hendrix and Heartbreakers concerts, and a long-distance swim with a friend in Finland who lives in a medical pod. If weeks of Facetime dinner dates, Netflix watch parties, and Skype happy hours have you feeling down while you shelter in place, consider accepting Estrada’s invitation to revel in the creativity and intimacy that Elizabeth and Carlos find together online.

Jenny Odell, How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy (Melville House, 2019)

In Jenny Odell’s hands, “nothing” isn’t nothing at all. In her celebration of “doing nothing,” Odell makes a compelling argument for the reclamation of time, labor, and attention that resists the demands of capitalist productivity and optimization. Moving effortlessly from the merits of going on a walk without a destination, sitting in a rose garden, birdwatching, and making (or looking at) art made from recovered “trash” to the politics of non-monetizable free time and the ethics of non-commercial public space, How to Do Nothing is a smart and readable treasure trove of wide-ranging insights about connection and care. For anyone feeling the pressure to “optimize” their quarantine time or turn work-from-home into work-around-the-clock with often-uncooperative “coworkers” (children, roommates, companion animals), Odell’s book—and her delightful talk—will feel like a pressure release valve. Read How to Do Nothing alongside Harryette Mullen’s Urban Tumbleweed: Notes from a Tanka Diary (2013), a collection of short poems inspired by Mullen’s solitary ambles through the streets of L.A., and consider taking them along as companions for a stroll around the block.

Petra Kuppers, Gut Botany (Wayne State UP, 2020)

Petra Kuppers’s new collection is a wonder. The publisher’s page quite rightly describes Gut Botany as “a queer ecosomatic investigation” that asks readers to “navigate their own body through the peaks and pitfalls of pain, survival, sensual joy, and healing.” Kuppers lavishes attention on both places and bodies—human, more-than-human, her own — as the book charts her movements through a world alive with wounds and unexpected beauty. Poems like “Moon Botany” offer a wheelchair user’s view of insects, fruiting fungi, and plant life while “Court Theatre” invokes Kuppers’s performance-activism following her sexual assault. Throughout, her collection embraces inclusivity and entanglement; nothing and no one here functions in isolation. The book is often energized by collaboration and conversations with other artists: poet Bhanu Kapil, dancer/poet Stephanie Heit (with whom Kuppers worked on the “Asylum Project”), and visual artist Sharon Siskin join the community on the page. And Kuppers also invites readers to consider their own somatics: what is it to be in this body, here, now? At turns beautiful and provocative, Gut Botany is a tonic against loneliness.

Living In (and Beyond) Dread

Jenny Offill, Weather (Granta, 2020)

Lizzie Benson, a librarian in New York City, has spent the last few years caring for her mother, supporting her brother in his addiction recovery, and doing her best for her marriage and her young children. Just as everything starts to seem under control, her mentor, Sylvia Liller, hires Lizzie to respond to the flurry of email she receives now that her climate change podcast, Hell or High Water, has made her a household name. As the nation’s already polarized political situation worsens and global crisis feels increasingly imminent, Lizzie becomes obsessed with learning end-time survival strategies—if only the mundane difficulties of work, family, and everyday middle-class life would give her time to commit to doomsday prepping and binge-watching Extreme Shopper. Written in short lyrical fragments, the timely novel offers a witty portrait of living under clouds of existential dread while still showing up for loved ones and getting through the day. Even if you’re not the type who understands the impulse to build a doomstead bunker and clean out the local grocery store’s entire toilet paper stash—or who, like me, stocked up on dried beans last week—you’ll find much to love in Offill’s funny and beautifully-crafted book that refuses to make light of anxiety and insists on the possibility of weathering whatever comes next.

Larissa Lai, Tiger Flu (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2018)

Tiger Flu is a sci-fi pandemic novel unlike any other. Lai’s most recent novel follows two entwined narratives: Kora Ko is a “starfish”—a woman who can regenerate limbs—who lives in one of four quarantine rings in Salt Water City (circa 2145), where a disease known as the tiger flu is ravaging its male victims; Kirilow Groudsel is an apprentice doctor who lives in Grist Village, an exiled community of parthenogenic women, who heals her sisters by surgically transplanting body parts of starfish who consent to the procedures. When the starfish living in Grist Village dies from an infection, Kirilow heads to Salt Water City in a haze of anger and grief to search for another. As she tries to convince Kora to join the Grist community, the two are abducted for use in scientific experiments by men who are hell-bent on learning how to separate the mind from the body in order to survive the disease. If you’re in the mood for pandemic reading with a queer feminist biopunk twist, Tiger Flu will not disappoint.

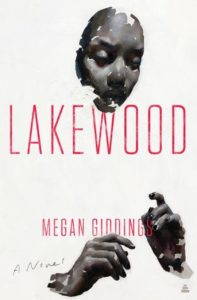

Megan Giddings, Lakewood (HarperCollins, 2020)

Megan Giddings’s debut novel Lakewood follows Lena Johnson, a young Black student who leaves college in the wake of her grandmother’s death in order to support her ill mother and pay off the family’s mounting debts. She takes a surprisingly well-paying job that offers health insurance and housing for her entire family and asks only that she join a series of secret experiments called The Lakewood Project. As the novel progresses, The Lakewood Project begins to resonate with a long and terrible history of private and government science using Black bodies as objects of study—Henrietta Lacks and the men of the Tuskegee syphilis trials are just two famous examples among so, so many. And Lena is faced with an impossible choice: continue to participate in increasingly horrific medical experimentation or leave the “job” and face the threats of poverty and houselessness in a remote Michigan town. Amid the recent buzz about how COVID-19 has revealed the systemic fault lines that leave the most vulnerable people in the United States without access to care, Giddings’s deeply moving and page-turning horror novel confronts readers with the fact that too many working-class, Black, and marginalized people have been falling (pushed) into these cracks all along.

Care in Uncertain Times

Tangerine Jones, #Ragebaking and #TheOriginalRageBaking

If you’re not already following Tangerine Jones on Instagram— #RageBaking, #TheOriginalRageBaking— now would be a great time to start. Inspired by a long lineage of Black women whose kitchens and kitchen tables have been at the center of community care, empowerment, and political resistance, Jones describes the personal and political stakes of the Brooklyn-based project: “I’m ragebaking to combat hate, keep my stress levels down and put some good in the world.” The fundamentals of ragebaking—the ragebaking rules—invite aspirational ragebakers to confection with intention and kindness, to experiment, to embrace failure, and to share what and whatever they can with others. In difficult times, Jones holds onto hope through everyday activism: “there are ways to nourish ourselves and others,” she writes. “It’s possible for us to all get fed—bellies, hearts and minds.”

Natalie Diaz, Postcolonial Love Poem (Graywolf, 2020)

True to its title, love and desire drive Natalie Diaz’s second collection—a book in which land, waters, brothers, lost and murdered women, lovers, and the Indigenous, Latinx, Black, and brown women of America count among the poets’ beloveds. The book bristles with unflinching descriptions of historical and ongoing violence against Indigenous communities and rails against Native erasure. And it is tender in its pleasures, sensuality, and joys: “Let me call my anxiety, desire, then. / Let me call it, a garden.” In Diaz’s thrilling new collection, self-care is community care and self-love, community love, all faithfully tended to grow into new and better futures.

Hi‘ilei Julia Kawehipuaakahaopulani Hobart and Tamara Kneese, “Radical Care: Survival Strategies for Uncertain Times” (Social Text, 2020)

The introduction to this Social Text issue on “radical care” will encourage you re-think what you know about taking, giving, and sharing care with others. As tempting as it is to romanticize care as always radical — as a “natural” outgrowth of love rather than work — Hobart and Kneese remind readers that it too “is inseparable from systemic inequality and power structures.” Commodification diffuses the politics of self-care into bubble baths, gym memberships, and destructive cycles of feel-good capitalism. Community care often relies on the unpaid labor of already marginalized people to fill gaps created by institutional neglect. Care without reciprocity and solidarity can pit some groups against others to determine “who is worthy . . . and who is not.” Practices of radical care aim for nothing less than to “rebuild worlds” for those who “dare to thrive in environments that challenge their very existence.” The entire issue is brilliant, but it’s behind a paywall. The introduction is available for free. For any one who is reconsidering how to relate ethically to others— who and how to be during a global crisis— “Radical Care” both binds us together and lets the light in.

Featured image: Crown shyness in Plaza San Martin, Buenos Aires. Photo by Dan Peak, 2003.

Addie Hopes is a Ph.D. candidate in Literary Studies at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and a member of the Edge Effects editorial board. She’s spent the last week in her pajamas following the CDC’s advice to stay home, reading fantastic new books to stave off cabin fever, and distracting herself from writing a dissertation about contemporary environmental docu-poetry with cats, family Zoom dates, and solo dance parties. She holds an M.F.A. in Fiction from Brooklyn College, CUNY. Her recent contributions as an Edge Effects author include “Nine Women Who are Re-Writing the Environment,” “Toxic Bodies and the Wetter, Better Future of Mad Max: Fury Road,” and “Ode to the Madison Lake Monster.” Twitter. Contact.

You must be logged in to post a comment.