The Rise and Demise of Equine “Cyborg” Labor

Humans have entangled their lives with horses for thousands of years. In recent times, however, people often forget that only two lifetimes ago, horses were inseparable from daily life. In the United States—and many other countries—horses were not only deeply entwined with human social worlds, but also performed labor indispensable to their economic and political worlds: plowing fields, fighting wars, hauling materials, transporting people and goods, delivering necessities, and mobilizing fire and police departments.

Until around 1930, horses were deeply integrated into infrastructural systems. They performed what Donna Haraway calls cyborg labor—work in which humans, horses, and equipment merged into hybrid, mechanized forms. These cyborg assemblages were central to the development and expansion of U.S. cities. Despite their pivotal role, horses were gradually displaced by automobiles and relegated to the nostalgic imagination.

How can we complexify a city like Madison, Wisconsin, by revealing nuanced, beyond-human relationships at the onset of the automobile age?

Equine Cyborg Laborers

From 1860 to 1900, horse populations in the U.S. grew from seven million to nearly twenty-five million. In this transitional period, horses transported people (via omnibuses and liveries), goods (on drays and delivery carts), and essential services (for police and fire departments) throughout cities, including Madison.

At this time, most people considered horses “mechanical laborers”: living bodies that could be treated as if they were inanimate machines. Horses were favored as labor animals because they were intelligent, easy to train, and were mistakenly believed to feel little fatigue, pain, or emotion.

Beginning in the 1860s and continuing well into the twentieth century, numerous investigations were launched to “mechanize the natural,” or better understand how horse bodies could be harnessed—literally and figuratively—as efficient mechanical technologies. So-called “horse motors” were often promoted as more efficient and less costly than “water-power” steam engines.

Madison’s rapid industrial expansion would not have been possible without these working horse companions.

There was room for humans to view horses as loyal partners and fellow laborers. The scientific aim in studying horse biology, however, was not to make work horses more comfortable but to maximize the efficiency of the “biochemical engines” that horses constituted, to perform as much labor in as little time as possible without “giving out” (a very expensive loss).

Achieving maximum efficiency meant learning how to attach labor-capturing implements to horse bodies. By the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, nearly all work horses wore equipment such as harnesses or saddles, bridles with metal bits, and reins so that humans could more easily control horses’ movements. Together with this equipment and their drivers, horses became cyborg laborers—fused entanglements of living and nonliving material. A dray cart, for example, is an assemblage of species, beings, and objects that cannot be easily unraveled. Multispecies histories always resist easy categorization.

Horsepower in Madison

Horses are not strongly associated with Midwestern cities like Madison. However—or perhaps because of this—it is important to consider equine influence there and across urban spaces in the U.S. Sanborn maps and archival photographs of Madison illustrate how pervasively cyborg horse labor aided human expansion. As a result, equine infrastructure prominently shaped how the city is arranged today.

As Madison’s population rose rapidly beginning in 1840, so did the need for horses. Many of the city’s equine-centric businesses were located close to Capitol Square, where horses were marketed until around 1890 (when the operation then moved to the water tower on East Washington Avenue). The Water Tower Horse Market took place the first Wednesday of every month from 1890-1906, bringing in many Midwestern horses and humans.

In this expanding Madison, cyborg, horse laborers were used mainly for the transportation of people, goods, and services. City living did not allow for the land needed to support a family horse. Instead, people relied on third-party transportation with large fleets of horses, like omnibuses and liveries.

Omnibuses, which evolved from the stagecoach, operated much like modern public transit systems: Patrons paid to travel via fixed routes and schedules. Although affordable, omnibus lines were notoriously bumpy. The horse-drawn streetcar, or horsecar, was therefore a welcomed innovation in the Madison urban landscape.

Horsecars ran on tracks—a mechanization illustrative of the equine cyborg assemblage—so the rides were more comfortable for human patrons and the horse laborers could more easily pull heavier carriages. Horses also decreased the cost of omnibus rides, since a single horse could successfully pull a horsecar. Because horsecars made longer distance travel easier, more comfortable, and cheaper, they allowed for a more sprawling urban landscape.

Conversely, livery stables rented out private carriages. Renting a carriage was expensive, so liveries catered to luxury consumers and special occasions. Madison had an astonishing seven liveries in 1885, all located near Capitol Park or State Street near streams of wealthy potential customers.

As the population grew and sprawled, emergency services and goods like beer and milk needed to be transported over longer distances, requiring horses to pull heavier loads. Madison’s fire and police departments relied on such horse-drawn vehicles. The fire departments started integrating small trucks into their fleet in the 1920s but continued to use horse-drawn vehicles alongside automobiles until 1934.

The multispecies cyborg assemblages that labored to expand Madison and its surroundings shared a common decline, as horses and humans alike struggled to keep up with Progressive ideals and new technologies.

Much like the horse-drawn vehicle itself, daily milk delivery is now a bygone tradition in most American communities. But in the nineteenth century, Madison’s Kennedy-Mansfield Dairy Company used a cyborg equine fleet. Early-twentieth-century photographs of the Kennedy team show uniform drivers and horses, pulling wooden-wheeled wagons that worked well on hard-packed dirt roads installed specifically to accommodate fragile equine hooves and legs. Much like the fire department, by the mid 1930s, trucks began replacing the horse-drawn wagons of Kennedy Dairy.

Madison breweries also relied on horsepower—not only for delivery, but also production. Before Fauerbach and Breckheimer’s breweries converted to mechanized boilers in 1890, horses provided the energy needed to produce beer. Fauerbach’s brewery even won awards for their cyborg assemblage delivery teams, but refrigerated trucks began replacing horsedrawn carriages around 1930.

Horses made Madison’s businesses run, and blacksmiths and harnessers helped keep those horse laborers moving. Madison’s blacksmiths and harnessers ensured horses had proper shoeing, tack, carriages, and carts to perform critical urban work. Harnessers provided tack like bridles, bits, harnesses, and reins that connected human to horse, completing the laboring cyborg assemblage. In 1885, there were nine blacksmith shops in the seven square blocks from East Washington Avenue to East Wilson. That’s more than one blacksmith per block in the heart of the city! Properly fitting tack and shoes were essential to equine wellbeing, but also part of mechanizing the natural: comfortable horses worked better and faster.

Adolph Frederick Schmidt owned one of the oldest tack shops in Madison, which he opened in 1909. The shop remained open until 1957, when Schmidt retired at 81. As Elizabeth Alanne reported for the Wisconsin State Journal, “After nearly half a century of harness-making in a city that has become an industrial center, Adolph Schmidt will close the doors—not only on a harness and saddlery shop—but on an American era.”1

The Changing Horse

Maps and stories from Madison reveal a pattern: The era of cyborg horse labor between 1880 and 1920 was followed by first a gradual integration of automobiles and then a complete takeover in the 1930s.

A progressively auto-centric infrastructure posed challenges for Madison’s horses. Many downtown streets, including University Avenue, were paved from the mid-1920s. Sleek pavement worked better for heavy cars to tread over, even if horses risked slipping or skidding. As a result, wooden wagon wheels on horse-drawn carts switched to pneumatic tires similar to those used on cars, and cart drivers were vigilant for their laboring companions.

September 1944 was the last time a Kennedy Dairy draft horse made a milk delivery in Madison, because as horse-keeper Matt Marty said, “Trucks’re just too much for ‘em. Everybody’s in a hurry these days.” The dairy industry was the last large-scale horse operation in Madison to close its stable.

Also changing around this time were the perceptions of horses as laborers, and as animal beings. In the Progressive Era beginning in the 1890s, intellectuals began to critique animal power as unsanitary and dangerous. Manure cleanup became particularly divisive, as piles of it were thought to attract houseflies and other disease-carrying pests.

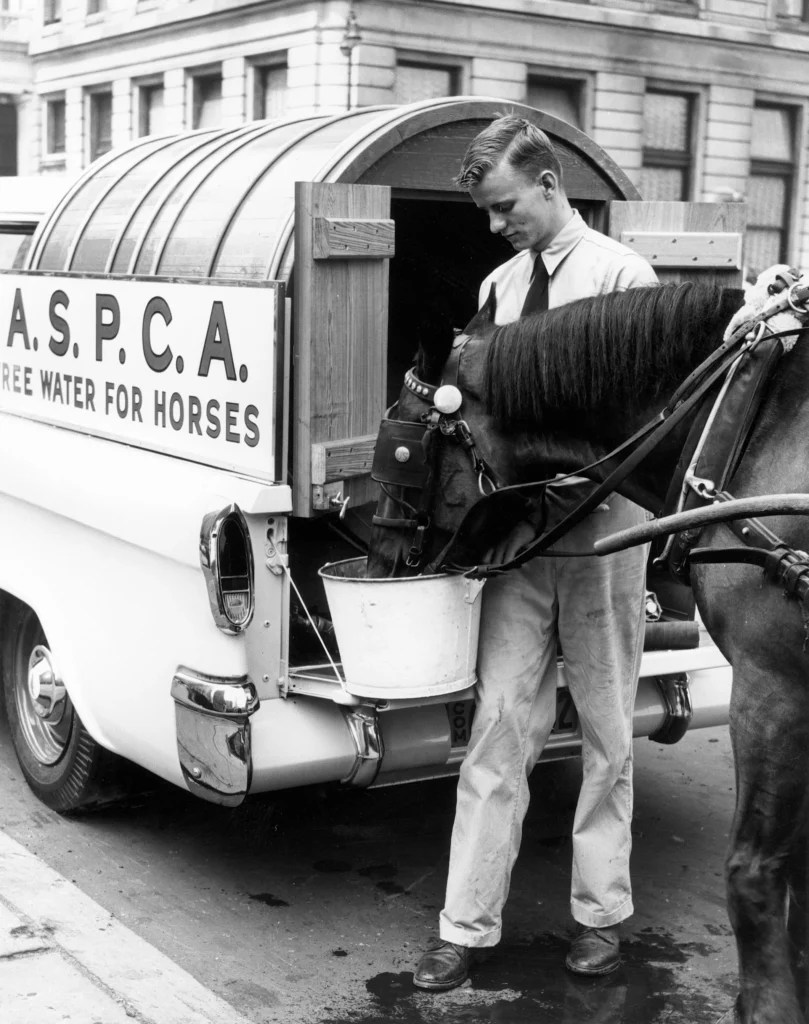

At the same time, animal welfare groups like the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (now ASPCA) advocated for more humane treatment of animals. These groups gained popularity as horses began pulling heavier, longer loads to sustain urban sprawl.

The confluence of animal rights activism and automobile championing meant the disappearance of horse labor. The 2.5 million registered cars roaming the streets by 1910 left urban horses with little use. Horse companions—even cyborg ones—simply could not compete with the ease, convenience, and affordability of automobiles. Mechanic efficiency, sanitation, and animal welfare ruled the midcentury and beyond.

By 1960, only three million horses remained in the United States, the majority kept for recreation and sport. As the era of equine cyborg laborers closed, a new era of equine athletes, entertainers, and pets was beginning. Horses became nostalgic rather than efficient.

In 1936, the Parkway Theater ceremoniously gifted a bale of hay to Ned, the oldest Kennedy delivery horse in Madison, retired as part of the last generation of Madison delivery horses.

From the Equine Era to the Engine Era

For years, urban horses like Ned served not only as trusted cyborg laborers, but as coworkers to their human companions. They shared the road with cars and streetcars, but were increasingly forced to use the outside lanes near the curb. A Kennedy horse called Lady reportedly learned the colors of the stoplights and “wouldn’t cross the street unless the light was with her. Just try to find a truck with that many brains!”2

At this time, most people considered horses ‘mechanical laborers’: living bodies that could be treated as if they were inanimate machines.

The 1942 Sanborn map of Madison showed vast changes. Rather than harnessers, farriers, and feed stores, there were now specialty tire shops. Carriage houses were replaced by automobile garages. The Riley & Co. livery transitioned from selling carriages in 1885 to selling and servicing Oldsmobiles by 1930, just as the Fashion Boarding Stables was converted into an auto sales and service shop with an attached parking lot. In fact, during this transitional period, some automobile garages were advertised as “auto liveries.”

The energy of Madison (literally and metaphorically) was changing with the onset of the engine era, for horses and humans. The multispecies cyborg assemblages that labored to expand Madison and its surroundings shared a common decline, as horses and humans alike struggled to keep up with Progressive ideals and new technologies.

As cyborg horse labor quietly disappeared, the multispecies awareness that came from sharing proximal space did as well. By 1950, the social influence of horse labor was completely gone from Madison.

However, horses left a lasting mark on the city. Madison’s rapid industrial expansion would not have been possible without these working horse companions. Horses themselves are no longer visible in present-day Madison’s urban geography. But its history, and cities like it, must be understood as more-than-human—entangling human, horse, and mechanical labor into one complex, inseparable connection.

Featured Image: Ned, the oldest dairy delivery horse and part of the last generation of delivery horses in Madison, is gifted a bale of hay by the Parkway Theater. Photo by Angus B. McVicar, 1936, digitalized by Wisconsin Historical Society.

Bri Meyer is an anthropology Ph.D. and former Managing Editor of Edge Effects. She is now a research communications specialist for the UW–Madison College of Engineering, where she translates cutting-edge advancements for public or policy audiences. Catch her in nature, at a bakery, or at the gym. Contact.

Referenced Articles:

You must be logged in to post a comment.