Living Writers on Revolution

Climate justice and environmental justice cannot coexist with white supremacy, police brutality, and anti-Blackness. These past weeks, Edge Effects editors have been sharing with one another books, essays, and conversations that chart paths toward revolution and racial justice in the US. We’re not alone in turning to books. Reading lists have flooded our social media feeds, highlighting Black authors and those working toward Black, queer, and trans liberation. Black writers currently fill the New York Times nonfiction bestseller lists, and Black environmentalists, climate activists, and environmental justice advocates have the mic. Environmental advocacy groups and environmental studies scholars are reckoning with the structures of white supremacy and state violence that still too often limit, ignore, and exploit the work of LGBTQ+, Black, Indigenous, and people of color. The list we share below hopes to add to this ongoing conversation.

It is not enough to read about revolution. That is only a start. As Christina Sharpe recently wrote on Twitter, “believe in reading. and also riots.” The ground may be shifting, but there is a long road ahead. We’re grateful to our readers and contributors. We’re mindful—and critical—of the institutions and communities in which we’re situated. We’re deeply respectful of local organizations like Freedom, Inc. and Urban Triage who have been working for racial justice here in Madison, Wisconsin long before this month and who will continue to push for liberation and equality long after. We’re remembering how N.K. Jemisin’s Broken Earth trilogy ends: “Don’t be patient. Don’t ever be. This is the way a new world begins.” We hope these writers help you imagine a better world and confront our own.

Kitanya Harrison—Disposable People, Disposable Planet (Uprise Independent Press)

Published in 2018, Kitanya Harrison’s collection of essays remains strikingly and unfortunately, relevant. As Harrison writes in the introduction to Disposable People, Disposable Planet: “Each essay in this volume discusses something precious that is being devalued. Black lives. The rain forest. Facts. Silence and solitude.” In the essay that gives the collection its title, Harrison takes the example of Hurricane Katrina to warn about the allures of revisionist history, of forgetting the recent past in favor of an easier, copacetic narrative that whitewashes ongoing violence and inequality. Many will find echoes of current conversations throughout the wide-ranging collection, which includes essays about Colin Kaepernick’s protests, the dangers of white feminism, and police brutality. In some ways, each essay circles around a common question about justice, crisis, and the possibility of collective change: “What are we prepared to do to survive?”

Ruha Benjamin—“Black Afterlives Matter” (Boston Review)

“In the U.S., our institutions are especially adept at resurrecting white lives that snuff out black ones.” So begins Ruha Benjamin’s essay, published in 2018, which shows how racism is reproduced by unjust and unequal systems that support white existence and cause Black death. The essay follows Black afterlives, both spiritual and environmental, and the alternative bonds of kinship that form within this “racist status quo.” Benjamin lyrically ties together her memories of living on the Marshall Islands as a teenager, a college classmate’s story about unwanted sterilization, the sci-fi TV show The Expanse, electronic surveillance, and prison abolitionism. The essay originally appeared in Making Kin, not Population and is also currently available online in the Boston Review.

Eve L. Ewing—1919 (Haymarket Books)

Like the excellent Electric Arches, Eve L. Ewing’s 1919 is a short, poetic book that rewards re-reading. Trained as a sociologist, Ewing has a deep interest in liberation and education that comes through in her experimental approach to history, mixing poetry with news clippings to suggest the too-often biased, racist, and incomplete perspectives of traditional journalism. 1919 is a genre-bending, gripping account of Chicago’s history, and tells the story of the July 1919 protests sparked by the killing of a Black teenager, 17-year-old Eugene Williams. Williams drifted into the “White area” of Lake Michigan, which was “unofficially segregated” (as one section of 1919 describes it) by white beachgoers throwing rocks at approaching Black swimmers. Williams drowned, and police officers failed to arrest those responsible. Who can safely enjoy the outdoors, whether swimming at a beach or birdwatching in a park? One hundred years later, the lines drawn in the sand remain too terribly similar.

Nick Estes and Jaskiran Dhillon (editors)— Standing with Standing Rock, Voices from the #NoDAPL Movement (University of Minnesota Press)

“No one could have predicted the movement would spread like wildfire across Turtle Island and the world, moving millions to rise up, speak out, and take action. That’s how revolutionary moments, and the movements within those moments, come about. Freedom and victory are never preordained.” Nick Estes and Jaskiran Dhillon describe in this collection’s introduction how the Indigenous- and women-led movement against the Dakota Access Pipeline was a continuation of “long traditions of Indigenous resistance deeply grounded in place and history.” The chapters testify to the collective and global strengths of this grassroots movement. David Uahikeaikalei‘ohu Maile’s contribution, for instance, links protests against the Thirty Meter Telescope in Hawai’i and the Dakota Access Pipeline in Standing Rock, particularly in terms of how the “U.S. settler state, with its multiple institutional forms, geographic locations, and individual agents, talks about violence.” The accounts of police, military, and private security forces confronting protestors with tear gas, pepper spray, dog attacks, water cannons, and drone surveillance speak to the enduring relevance of the issues of environmental justice and sovereignty raised by the Water Protectors.

Ruth Wilson Gilmore —Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California (University of California Press)

As calls for the abolition of prisons and police departments gain momentum, it’s a good time to consider what environmental justice has to do with mass incarceration in the United States. Scholar-activist Ruth Wilson Gilmore has been advocating for prison abolition for decades, and her writing is among some of the most powerful work on the subject. Her 2007 book Golden Gulag is a study of how surplus capital, labor, land, and state power fueled prison expansion in California. Gilmore’s extensive research traces how the world’s most extensive carceral project grew California prison populations 450 percent between 1980 and 2007, with young people of color disproportionately represented among the incarcerated.

As we look forward to the upcoming publication of Gilmore’s Change Everything: Radical Capitalism and the Case for Abolition (Haymarket Books, 2021), you might check out what she has to say about global abolition geographies, why prisons aren’t as necessary as you might think, and why the struggle for freedom needs to be part of the conversations about COVID-19. In a recent interview for Haymarket Books, Gilmore and Naomi Murakawa (author of The First Civil Right: How Liberals Built Prison America) discuss the pandemic and public health, racial capitalism, and the urgent need for decarceration for the millions of people in jails, prisons, and immigration detention centers.

Our Climate Voices—An Episode on Climate Justice & Queer and Trans Liberation

This episode of Our Climate Voices podcast— Climate Justice & Queer and Trans Liberation—brings together five queer and trans climate justice organizers. Meera Ghani, Orion Camero, Sophia Benrud, Mmabatho Motsamai, and Gabby Benavente invite listeners into a four-part series of moving and wide-ranging conversations that center queer and trans solutions to climate crises. In the first part, they tackle the intersections of oppression that put queer and trans people of color on the frontlines of environmental crisis and the importance of solidarity in the collective struggle for justice. The second considers how queer and trans voices are erased from the climate movement, and the third to looks to the past for lessons in revolution as they honor the lives and the legacies of Black trans activist Marsha P. Johnson and Latinx trans activist Sylvia Rivera in the Stonewall uprising and beyond. In the fourth and final part of this episode, the five activists each share their vision for a liberated future; in doing so, they not only describe how coalition and community might inspire a “transformational shift” toward justice, but they also create a model for the future as it could be now.

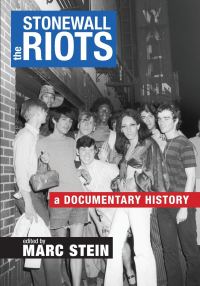

Marc Stein (editor)—The Stonewall Riots: A Documentary History (New York University Press)

A riot, a protest, a movement, a parade— what we call collective outrage and uprisings can shape reactions and reflect our own biases. Increasingly, many queer and trans activists are deliberately rejecting corporate-sponsored versions of Pride parades and whitewashed versions of Stonewall’s legacy and returning to the original revolutionary spirit of the Stonewall riot. The Stonewall Riots: A Documentary History is one of several collections that provide firsthand accounts of the decades before and after Stonewall, both the violent policing of LGBTQ+ people in the US and the flourishing communities that persisted in spite of this oppression. Marc Stein’s accessible introduction takes care to emphasize how there is “always more to the story” than what one single account of Stonewall can describe, and walks readers new to studying history through some of the limitations and benefits of reading both primary and secondary sources. The ebook is currently discounted at some online booksellers.

Saidyia Hartman—”The End of White Supremacy, An American Romance” (BOMB)

For those of us learning how to practice anti-racism as non-Black allies, it can be easy and comfortable to focus our attention exclusively on Black pain and trauma. Yes, allies must take responsibility for how the “stranglehold of white supremacy” produces social, political, and environmental injustices—how, as many have recently noted, the refrain “I can’t breathe” resonates with the ways that Black communities face outsized burdens in the face of climate change, pollution, housing, and public health as well as police brutality and the prison industrial complex. All too often, however, allies are drawn to narratives of Black victimhood that naturalize anti-Blackness as an unalterable reality rather than a set of built structures that can be—must be—un-done. In her recent BOMB magazine article, “The End of White Supremacy, An American Romance,” Saidiya Hartman considers the 2019 film Queen & Slim and a 1920 speculative short story by W.E.B. Dubois, “The Comet.” Written in the wake of the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918 and the Red Summer of 1919, “The Comet” is a tragic and hauntingly relevant story about a Black man in New York City who (at first) appears to be the sole survival of an environmental catastrophe. In Hartman’s hands, an unflinching look at white supremacy in the United States also celebrates Black creativity, resistance, and the “infinite playlist of love in a world where black life is all but impossible.”

Kathryn Yusoff—A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None (University of Minnesota Press)

It is no coincidence that environmental injustice and racial injustice coincide. What makes A Billion Black Anthropocences or None so compelling is the exacting detail, unrelenting incisiveness, and lucid clarity with which Kathryn Yusoff traces the shared origins of colonialism, slavery, and unsustainable resource depletion. Yusoff lays out how the devaluation of Earth’s biosphere and the devaluation of Black and Indigenous communities have issued from historically entwined “grammars of extraction.” Because academia, science, and popular environmental movements are not exempt from the violences wrought by these “grammars of extraction,” taking any form of environmentalism seriously also requires approaching issues of race, racism, and social injustice with an equal degree of rigor and personal commitment. The slim volume is available to read online for free until August 31, 2020.

Lauren Michele Jackson—”What Is an Anti-Racist Reading List For?” (Vulture)

Lauren Michele Jackson’s recent essay on anti-racist reading lists is at once timely and timeless. As publications rush to meet the moment of global protests against police brutality with well-intended suggestions for our bookshelves, Jackson takes a step back to think about the purpose, and effect, of recommendation lists (like this one). She points out that anti-racist reading lists presuppose “that books written by or about minorities are for educational purposes, racism and homophobia and stuff.” Writing of Toni Morrison, Jackson describes how “in The Bluest Eye racism is the environment—the weather, the climate—and it makes the seasons turn, which is to say that it is happening all the time and therefore no more remarkable than March snowflakes in the Midwest.” But this stunning novel, Jackson argues, is reduced and simplified if approached by a reader as “a balm for… latent racism.” Her skepticism is persuasive, and a reminder to teachers, scholars, and readers that anti-racist work must extend beyond a bookshelf.

Featured image: A protest in support of the Black Lives Matter movement in San Francisco, CA. Photo by David Goehring, June 2020.

For more reading suggestions, check out the rest of our recommendations.

You must be logged in to post a comment.