From TNT to Tallgrass: Prairie Restoration at a Munitions Plant Turned National Grassland

Roughly 38 miles southwest of downtown Chicago, the former U.S. Route 66 (now Illinois Route 53) winds its way through the gently rolling fields of Midewin prairie, past the rural village of Elwood, Illinois. A steady low rumble punctuates the prairie’s stillness; the din of diesel engines echoes across the landscape as trucks travel along the fabled “Mother Road” that once connected Chicago to far-off Los Angeles. New successors to this transportation heritage abound amid the cornfields. Just south of Elwood at the former Joliet Army Ammunition Plant (JAAP)—once the largest munitions plant in the world—where just three quarters of a century ago 10,000 workers manufactured explosives for the U.S. Army, a new industrial park boasts an intermodal facility where shipping containers laden with goods from around the world are transferred from railcars to tractor-trailers for distribution throughout the Chicago area. As I travel south along Route 53 to visit my grandfather’s gravesite at the Abraham Lincoln National Cemetery, also built upon former munitions plant grounds, I note the somber funeral processions that share the road with the boisterous truck traffic.

While it is impossible to entirely undo the effects of two centuries of agriculture, industry, and commerce on the landscape of Will County, the Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie—at 20,283 acres, the largest protected open space in the Chicago metropolitan area—has successfully restored more than 1,800 acres of the decommissioned Joliet Arsenal to its former prairie splendor. Less than 0.01% of Illinois’s original 21 million acres of prairie remains; public memory of the tallgrass prairie has all but faded into abstraction, a relic of a distant past. Prairies are extremely valuable ecosystems that teem with biodiversity, efficiently sequester carbon from the atmosphere in large quantities, are highly drought-resistant, and stabilize the soil, preventing erosion and siltation in streams and rivers. If we allow the prairie to become lost to history, we do so at our own peril. We lose part of what makes the Prairie State—and on a larger scale, the American Midwest—so special.

Entrance to the Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie headquarters and welcome center on Illinois Route 53, the former U.S. Route 66. Photo by Sean Thoel, 2017.

Roosevelt’s “Arsenal of Democracy” Comes to the Illinois Prairie

On December 29, 1940, as Hitler’s Luftwaffe rained ordnance from the night skies onto London, Franklin D. Roosevelt took to the airwaves to deliver one of his most famous fireside chats. President Roosevelt observed that the current production infrastructure of the U.S. defense industry was insufficient to meet the increased demands of the Lend-Lease program, which supplied war matériel to Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and other Allies as a means to prevent the Second World War from reaching American shores. Invoking the American “spirit of patriotism and sacrifice” in a call for the construction of new munitions production facilities, Roosevelt asserted that it was the duty of the United States to become “the great arsenal of democracy.”

Rumors of changes in American defense policy had already been circulating well before Roosevelt’s radio address. With global depression and job scarcity a very recent memory, power brokers throughout the country jockeyed for position, hoping to woo Ordnance Department land scouts and secure thousands of guaranteed government jobs. But how does one choose where to build an ammunition plant? As far as the Army was concerned, not all land was created equal. Proposed munitions sites needed to meet rigid criteria in order to be considered viable locations.

The site of the Joliet Arsenal (outlined in orange) in relation to the Chicago Metropolitan Area. Source: Google Maps.

The open farmland of Jackson, Florence, Channahon, and Wilmington Townships in southwestern Will County beckoned. Encompassing some 36,000 acres near the villages of Elwood and Symerton, the proposed arsenal site was farther than 200 miles from national borders and lay protected behind the Appalachian and Rocky Mountains, rendering it safe from enemy air attack. Flagstone, limestone, timber, and other building materials were located nearby.

Will County’s proximity to Chicago also promised a large pool of skilled and unskilled labor. Moreover, the area’s distance from the city provided a buffer zone to minimize the danger of accidental explosions near populated areas, and an abundance of cleared cropland ensured adequate space for expansion. An extensive transportation network of paved highways, railroads, rivers, and canals connected the region to a vast hinterland, enabling easy transport of munitions to both the Atlantic and Pacific coasts. Most importantly, several creeks provided water for the disposal of waste products inherent in the TNT manufacturing process. The availability of all these attributes within a single region convinced Army planners of the site’s fitness for military duty.

The main gatehouse of the former Joliet Army Ammunition Plant, long since abandoned, now stands adjacent to the Prairie View Landfill and an industrial park, all located on the former arsenal grounds near Midewin. Photo by Sean Thoel, 2017.

Farmers Oppose the Enlistment of the Land

The proponents of the proposed Joliet Arsenal were many; military planners, politicians, local business owners, and employment-seeking workers alike expressed their support. By September 1940—preceding Roosevelt’s “arsenal of democracy” speech by nearly three months—these boosters had actively promoted government land acquisition, and for a time, it seemed that all would go without a hitch. Migrant workers seeking employment poured into the area anticipating jobs on arsenal construction crews, staying in basements, barns, and boarding houses.

A weathered sign located just north of the entrance to Midewin’s headquarters on IL Rte. 53 illustrates the lingering presence of the tallgrass prairie’s past as the Joliet Arsenal. Photo by Sean Thoel, 2017.

But the arsenal’s construction did not bode well for the livelihoods of the hundreds of local farmers who resided on the proposed site of the munitions plant. While securing fair market value for their holdings ranked highly among the farmers’ concerns, their protests centered primarily upon their physical and sentimental attachment to the land itself. For many, their acreage had belonged to their ancestors since white settlement of Will County began in the 1830s, and no price could be placed upon it.

On the evening of September 24, 1940, more than 450 farm owners and their families gathered at a Wilmington dance hall and listened as Colonel R.D. Valliant from the Department of the Quartermaster General delivered the government’s final offer for purchase of the land. The terms were simple: the Ordnance Department would pay current market value for the land, but would not reimburse the farmers for their lost livestock or farm implements. Construction of the arsenal was to begin in thirty days, and the farmers could either accept the government’s bargain and leave peacefully, or be forced out. Powerless to resist the government, hundreds of families began their painful exodus from southwestern Will County as concrete bunkers, factory buildings, and miles of barbed-wire fences rose from the fields and pastures behind them. Just as the farmers’ ancestors had done 100 years before, a new landowner would use the landscape in dramatically different ways.

Today, some of the most visible traces of the farmers’ retreat from the land are the family cemeteries left behind, some of which are nearly as old as Will County itself. Government construction crews built the arsenal around existing burial plots rather than relocating them. Whether the farmers’ cemeteries were allowed to remain out of respect or expediency, they provide concrete representations of the former residents’ sentimental and physical ties to the land. Like signposts on the landscape, these somber legacies mark southwestern Will County’s transition from agriculture to industry, as the United States made preparations for world war and subsequent global leadership.

“Red Water” and the Ill Effects of TNT Production

A monument to the 52 munitions workers who perished in an explosion on June 5, 1942, stands on former arsenal land near the entrance to the Abraham Lincoln National Cemetery in Elwood, IL. Photo by Sean Thoel, 2017.

Work at JAAP was fraught with hazards, not the least of which was the ubiquitous threat of explosion. The slightest error in handling or packing artillery shells with TNT could—and did—result in disaster. On June 5, 1942, at 2:40 A.M., a massive explosion ripped through a loading-assembly-packing building at the arsenal. The blast’s shock wave broke windows and slammed doors in houses in Waukegan, over 60 miles away, and 52 munitions workers perished in the explosion.

Many of the dangers of TNT production at JAAP were not as immediately fatal as the explosion on that fateful June night, however. Between 1945 and 1976, the Army declared portions of the installation’s buffer zone to be in excess and subsequently sold or leased these areas to farmers who grew crops, grazed livestock, and hunted amid the increasingly obsolete munitions buildings. As the once-mighty arsenal began to outlive its usefulness, the landscape began its transition from one dominated by industry to a post-industrial wasteland of abandoned bunkers, roads leading nowhere, and aging infrastructure. Although still enclosed by miles of fences, the Joliet Arsenal’s borders became increasingly porous as the Army granted farmers and livestock access to formerly off-limits fields and pasturelands, allowing non-human nature more frequent contact with the toxic aftereffects of explosives production.

The Midewin landscape is dotted with hundreds of abandoned concrete ammunition storage bunkers like this one. Some of these bunkers have found new life as on-site storage facilities for dormant prairie seed. As luck would have it, both explosives and the seeds of prairie grasses are best stored in cool, dark, and dry conditions. Photo by Sean Thoel, 2017.

On November 7, 1984, Chicago Tribune writer Casey Bukro published an article that brought the environmental hazards of the Joliet Arsenal to the public’s attention. Cattle grazing on leased arsenal land were dying of starvation-like symptoms, poisoned by creek water tainted with a substance known as “red water,” a chemical byproduct of TNT production. Flushed away during the refining process, “red water” was collected in large outdoor lagoons for evaporation, and the remaining TNT residues were then incinerated. However, these holding ponds were prone to leakage into local streams and aquifers as they aged, slowly poisoning the animals that ingested the chemical runoff.

Midewin Restores the Prairie to the “Prairie State”

By the late 1980s, the defunct Joliet Arsenal, its usefulness outmoded by the emergence of new military technologies and changing political climates, had fallen from its former position of Cold War military-industrial titan into an eyesore and an environmental liability.

Environmental cleanup required the cooperation of the EPA, the U.S. Army, and the State of Illinois. Decisions in July 1987 and March 1989 (for the manufacturing and assembly areas, respectively) to place the former arsenal on the Superfund National Priorities List (NPL) marked another turning point in the history of the southwestern Will County landscape, and the beginning of its slow return from post-industrial brownfield into a flourishing tallgrass prairie. NPL funding facilitated the bioremediation of thousands of cubic tons of TNT-contaminated earth, as well as the disposal of asbestos and other hazardous materials found in the hundreds of buildings that dotted the arsenal’s landscape. With the signing of the Illinois Land Conservation Act in February 1996 by President Clinton, the Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie was born.

A hedgerow of Osage orange trees marks the border of a former hayfield at Midewin, a reminder of the land’s prewar agrarian past. Planted widely by farmers and ranchers throughout the United States as windbreaks and pasture hedges from the 19th century onwards, the Osage orange tree’s native range is the Red River watershed of Texas, Arkansas, and Oklahoma. Elimination of non-native and invasive plant species is just one of many obstacles to prairie restoration at Midewin. Photo by Sean Thoel, 2017.

Prairies cannot restore themselves. They require human labor and stewardship. While the financial burden of removing abandoned infrastructure and restoring native prairie flora and fauna to 20,283 acres of land is significant, Midewin’s most important task is reconnecting people with land from which they have been alienated for over seventy years. Simply put, unless the public has a reason to care about restoring the arsenal land—to sow prairie seed and to reap its benefits—all efforts are for naught. By establishing educational programs for schoolchildren, providing volunteer opportunities for prairie restoration, improving trail access for hikers, bicyclists, and equestrians, and reintroducing native bison to the land, Midewin has reconnected the public with the prairie, based on the notion that people will be good stewards of an ecosystem in which they have a vested interest.

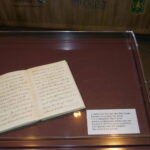

A 1942 quote from Aldo Leopold’s manuscript “Prairie: The Forgotten Flora” greets visitors to Midewin. The ecological practice of prairie restoration originated with Leopold’s work on the Curtis Prairie at the University of Wisconsin–Madison Arboretum in 1935. Midewin’s mission to reconnect people with the prairie takes to heart Leopold’s invocation in A Sand County Almanac: “We grieve only for what we know. The erasure of Silphium from western Dane County is no cause for grief if one knows it only as a name in a botany book.” Photo by Sean Thoel, 2017.

Environmental historian Paul Sutter has argued that all landscapes in which humans coexist with nature—whether a Boston street, the Grand Canyon, or a former ammunition plant in Illinois—are, in fact, hybrid. Embracing this idea allows us to distance ourselves from the flawed concept of pristine nature as a benchmark for a healthy environment. Instead, Sutter posits, hybrid landscapes enhance our relationship with the environment by allowing the natural world to be found “thriving in places swamped by human activity.” In the case of Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie, this is the literal truth. Surrounded by the ever-present sprawl of suburban Chicago, Midewin—named for a Potawatomi word that means “healing”— stands as a testament to sustainable hybridity. By empowering Americans to become active participants in the prairie’s restoration and educating them in its proper stewardship, Midewin has embraced the public as a vital component of the Illinois tallgrass prairie ecosystem’s successful return, rather than pushing it away. With each handful of prairie seed that is sown at Midewin, with each new bison calf that is born, Americans have the opportunity to become investors in future generations, who will reap the dividends of our restoration efforts.

Featured image: Midewin’s landscape is dotted with hundreds of abandoned munitions bunkers such as this one in Group 63. Sometimes referred to as “igloos,” these bunkers were built with reinforced concrete walls nearly two feet thick at the sides and roughly fifteen inches thick at the top. Partially buried in topsoil and laid out in a staggered pattern, these bunkers were designed to direct the force of accidental explosions upwards rather than outwards, thus preventing an explosion from triggering a chain reaction with nearby bunkers. Removing these structures is costly—demolishing a single “igloo” can cost upwards of $50,000. The steel blast doors are also lined with asbestos, posing additional environmental hazards. Photo by Sean Thoel.

Sean Thoel is a Ph.D. student in History at University of Wisconsin–Madison. His research interests include the history of the Soviet Union, post-Soviet Russia, and modern Poland, with a focus on the environmental after-effects of Stalinist industrialization and Cold War technological advancement. Twitter. Contact.

You must be logged in to post a comment.