Chicago’s Deep History of Vegetarianism: A Conversation with Connie Johnston and Kay Stepkin

Chicago is often remembered for meatpacking, since Chicago’s Union Stock Yards at one point produced a majority of the meat in the US. But the city also has a less well-known connection to vegetarianism. Kay Stepkin grew up in Chicago, born to a meat jobber father who worked with hot dog stands and grocers. Though as a child she would regularly come home to a cow tongue boiling in a pot in the kitchen, Kay opened Chicago’s first vegetarian business in 1971, The Bread Shop, and founded the National Vegetarian Museum in 2016. Geographer Connie Johnston, on the other hand, always felt a kinship with nonhuman animals and has looked to understand others’ attitudes toward farmed animals through her academic work. Bridging their different perspectives, Kay and Connie aim to contest a monolithic story about the United States as a meat-eating country and celebrate the long history of vegetarianism and growing communities of vegetarians.

I spoke with Kay Stepkin and Connie Johnston in June 2019. We discussed Kay’s unlikely path to becoming a vegetarian (inspired by a James Bond novel), how restaurants and vegetarianism have changed in the past half century, and the current goals of the National Vegetarian Museum.

Stream or download our conversation here. Interview highlights follow.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Interview highlights:

This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Rachel Boothby: What prompted you to start the National Vegetarian Museum?

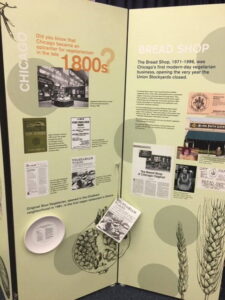

Kay Stepkin: Five or six years ago, I was invited on the Heartland Café’s radio show to talk about Chicago’s vegetarian history, which I thought I knew and which I thought I had started in Chicago. I talked about how The Bread Shop, which I opened in 1971, was the first vegetarian business in Chicago. After the talk went well, I started getting phone calls to speak at other organizations. So, I went online to learn more—and I thought I knew most everything, but maybe there were one or two little tidbits that I could learn. But it just blew my mind what I learned. Chicago has such a long, deep, and strong history. Our first vegetarian restaurant opened in 1900, the Pure Food Lunch Room. I don’t think many other people know that history. But, I thought, people have to know this. And that was the impetus behind the museum.

RB: Where can people find it, and what will they see when they do?

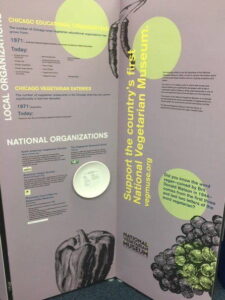

KS: We move every month or two. You can go to the museum’s website to find where we are presently. From the beginning, in my mind, we would start with a traveling exhibit. It was for practical purposes, because we wouldn’t have to pay rent. We don’t have to buy a building. Instead, we go to people. You don’t have to spend an hour crossing Chicago to see us. We go to all neighborhoods.

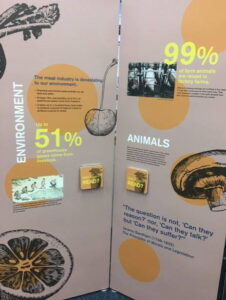

The museum itself consists of 12 interlocking panels, each about three feet wide by seven feet tall. Each of the panels covers a different aspect of our history, starting with the ancient world and going into Chicago’s great history in the 1800s, with the World’s Fair (Columbian Exposition). We have panels on famous vegetarians and on national vegetarian organizations. And our opening panel covers three main aspects of vegetarianism: health aspects, environmental issues, and animal issues.

Click to enlarge.

RB: Why does the US need a national vegetarian museum, and why now?

KS: I think it’s quite important. When I became a vegetarian, I did not know another vegetarian. I thought I was all alone. I think it’s important to know that we are part of a larger movement, and that the movement is thousands of years old. That knowledge gives us strength, and also allows people to know that they can learn from people that came before, and that they have the support of others in the movement. I think that is all quite important.

Connie Johnston: We have such a dominant narrative in the US of meat eating, and the National Vegetarian Museum is about interjecting a narrative that contests that monolithic one of meat eating. The museum makes it known that, as Kay was saying, there is a history of vegetarianism. There is a strong and vibrant and growing vegetarian community. It’s not something that just started a few decades ago, but has been part of the US for quite some time. We may be smaller in many ways than the dominant dietary perspective, but we do exist and have existed. There is a story to tell there. There is a history, there is a community, and it may be smaller, but it is not marginal. And it’s getting less marginal as we move through time.

Chicago’s history of meatpacking is legendary, but the National Vegetarian Museum challenges that familiar narrative. Postcard via the New York Public Library.

RB: What do you hope that individuals who visit your exhibit will take away?

KS: Well, as Connie mentioned, I hope they take away the realization that vegetarianism has always been a part of human culture. Our history is deep and it’s strong. Also, I hope that they take away the fact that our great movement is really exploding, not only in Chicago but all over the planet. And that they take away the knowledge of the interconnectedness between our environmental problems, our health problems, and the horrible conditions in which we raise our animals. All of that is connected and has a solution.

RB: Connie, you study social ideas about farm animal welfare. What brought you to this topic in your own work, and how did your work bring you to Kay and the National Vegetarian Museum?

CJ: I have always been interested in nonhuman animals and our human relationships with them. As a child, I felt a real kinship with nonhuman animals and I was curious as to why everyone didn’t feel as I did.

When I began studying for my Ph.D., I initially thought I would look at animals in medical research, but I shifted to looking more at industrial agriculture, farmed animals, and our relationship with those animals. I’m interested in what we learn about animals through science, but also how Western science tends to take a very exploitive attitude toward animals. How do we get ideas about what their welfare is, or what their capacity for sentience is? Part of my dissertation research was interviewing farm animal welfare scientists in both the US and in several locations in Europe. Many had a desire to make these animals’ lives better. They were not necessarily vegetarian themselves, certainly not vegan. Some of them worked in very close partnership with animal producers, but they all felt that, in some way, they were concerned with welfare and they were trying to make these animals’ lives better and that, in a lot of ways, bridged a divide.

When I began studying for my Ph.D., I initially thought I would look at animals in medical research, but I shifted to looking more at industrial agriculture, farmed animals, and our relationship with those animals. I’m interested in what we learn about animals through science, but also how Western science tends to take a very exploitive attitude toward animals. How do we get ideas about what their welfare is, or what their capacity for sentience is? Part of my dissertation research was interviewing farm animal welfare scientists in both the US and in several locations in Europe. Many had a desire to make these animals’ lives better. They were not necessarily vegetarian themselves, certainly not vegan. Some of them worked in very close partnership with animal producers, but they all felt that, in some way, they were concerned with welfare and they were trying to make these animals’ lives better and that, in a lot of ways, bridged a divide.

When I moved to Chicago to take a position at DePaul in the fall of 2016, I was at a vegetarian-related event that fall and just happened upon a display from the National Vegetarian Museum. I must have written my name down, because I was contacted sometime later by Kay. I was very intrigued by the Vegetarian Museum and felt that it was a different kind of organization, taking a different approach by focusing on the culture of vegetarianism. This was something that I was intrigued by and felt like, as an academic, I could perhaps be useful.

RB: It’s often said that when Upton Sinclair wrote The Jungle he was aiming for people’s hearts but instead hit their stomachs. I’m curious to know your thoughts on engaging with people’s hearts versus their stomachs.

RB: It’s often said that when Upton Sinclair wrote The Jungle he was aiming for people’s hearts but instead hit their stomachs. I’m curious to know your thoughts on engaging with people’s hearts versus their stomachs.

KS: Any way you can reach people about these issues is the right way. There’s a lot of ways we can reach people. There’s a lot of variety in the people that we’re reaching, and different people will be motivated by different aspects of what we’re trying to do. Some people are interested in their health, some in animals, others have mainly environmental concerns. It all takes us to the same place in the end and it’s where we need to go.

CJ: Sinclair’s book was originally an exposé of worker conditions in the Chicago slaughterhouses. A number of people have said that after they read The Jungle that they were more moved by what he described as happening with the animals. I know that certainly was the case for me. As Kay was saying, you reach people in lots of different ways and people will be moved in lots of different ways. We can’t disentangle the lives of the workers in slaughterhouses from the animals that were there. They were both being exploited. Today it’s the same situation, and the natural environment is being exploited by industrial meat production. Different aspects of these issues will resonate with different people. As someone becomes aware of problems, they will touch the thread that leads them to these other problems as well. So, whether you start out with the heart or the stomach or the head, those pieces are all connected.

Featured image: According to Kay Stepkin, Chicago’s first vegetarian restaurant opened in 1900. This postcard depicts Chicago in the same period. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

Kay Stepkin is the founder of the National Vegetarian Museum, a vegan chef, recipe creator, and a pioneer of the vegetarian and natural food movements in Chicago. In 1971, she founded the legendary Bread Shop on North Halsted Street, the city’s first modern-day vegetarian food store and only 100-percent whole grain bakery as well as the restaurant, Bread Shop Kitchen, across the street. The Bread Shop served as a training ground for aspiring chefs and bakers who went on to open restaurants and bakeries of their own. Stepkin was also the host of the 8-episode series “Go Veggie!® with Kay” that aired on Comcast cable and wrote “The Veggie Cook,” a bi-weekly column for the Chicago Tribune, for over 4 years. Website. Twitter. Contact.

Dr. Connie Johnston is a professional lecturer in the Department of Geography at DePaul University in Chicago. Dr. Johnston’s broad scholarly interests concern the relationships between humans and nonhuman animals. She is interested in the ways in which the state of scientific knowledge about animals at any one time shapes those relationships. Much of her research to date has focused on societal attitudes toward farmed animals and their welfare in the US and Europe. Dr. Johnston has given talks on the topic of industrial animal farming and is the author and co-author of a number of publications about human-animal relationships, including Humans and Animals: A Geography of Coexistence (ABC-CLIO, 2017), “The political science of farm animal welfare in the US and EU” in Political Ecologies of Meat (Routledge, 2015), and “Geography, Science, and Subjectivity: Farm Animal Welfare in the US and Europe” (Geography Compass, 2013). Dr. Johnston is also on the Board of Directors of the National Vegetarian Museum. Website. Contact.

Rachel Boothby is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Geography at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. She studies the cultural geography of the American food system and consumption more broadly from a historical perspective, from the farm-to-table restaurant movement to Lunchables. Rachel was a founding editorial board member and former managing editor of Edge Effects, and is currently working with the Center for Culture, History, and Environment at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Her most recent contribution to Edge Effects was “A Pig Born a Commodity, Raised as a Friend in Neflix’s Okja” (April 2018). Website. Contact.

You must be logged in to post a comment.