On Care in Dark Times

The warmest place, come January, that I’ve ever lived is Ithaca, New York. It’s a ridiculous thing to say, I’ll admit, because everyone knows that Ithaca is ravaged by brutal winters. If you’ve been in college towns long enough, you’ve probably seen the ubiquitous kelly-green t-shirt proudly proclaiming that “Ithaca is Gorgeous,” and it is, especially in the spring when the town is overtaken by yellow-blooming forsythia. What you might not have seen, though, is the famous shirt’s snide sibling, the black one that reads, “Ithaca is Cold.” But it’s not. Not really. Not the way that my grandmother, who was a student at Ithaca Conservatory in the 1940s knew winter: a time of cold that brought snowfalls deep enough for war-weary students to leap into from the roofs of their houses; cold enough for town residents to carom down Buffalo Street’s wickedly-pitched, arrow-straight course on toboggans when all the cars were snowbound. But Ithaca isn’t cold any longer. In the winter, it’s now mostly slushy and damp.

A few years ago, back before my family and I moved to Madison, Wisconsin (where it still occasionally gets frigid) I sat thinking, watching the annual January mildew leaf out into one-dimensional blooms on the dingy walls of my grad-student basement office. I had been reading Dipesh Chakrabarty’s “The Climate of History: Four Theses,” but had wandered off on the current of Chakrabarty’s thinking. Chakrabarty is an intellectual historian, and in “The Climate of History” he bent his mind around the implications of the story giving life to the word, “Anthropocene,” the age of human-induced global change. Never before in the history of the world, Chakrabarty pointed out, have humans assumed the sort of power historically reserved only for geologic forces like tectonic plates. Which means that the idea of the Anthropocene disconnects the known human past from the unprecedented present and unknowable future. Many of us have long heard that global climate change threatens the end of nearly everything we as a species have come to know: the predictable, Farmer’s Almanac return of frost-free planting weather; the ocean currents driving fish and powering local climates; the seasons for storm and drought, snowfall and ice-out, heat waves and cold snaps. Yet Chakrabarty was suggesting that the story of the Anthropocene is a crisis not just for life, but also for thought. I had never considered that. I had never considered that the Anthropocene could be a crisis of historical storytelling.

I watched for a long while, adrift as the mildew sent a deviant black tendril arcing out along the baseboard. There’s something about the story of the Anthropocene—of humans standing on the verge of an entirely new world—which sounded oddly familiar, and it slowly dawned on me that its general plotting is the same as the well-worn tale of modernity and capitalism, of rational, technologically equipped humans conquering nature, ushering in a new golden age. Only, this time, the story is flipped on its head, not a tale of triumph but a wail of lamentation: we’ve poisoned the garden, our only home, even as we thought we were engineering a newer, sleeker, better one, and we’re now awakening to the cold dawn of expulsion from everything we’ve known. These stories onto which Anthropocenic change has been grafted are very old: one a tale of Prometheus, the Greek titan and giver of light, the patron saint of science and technology; the other a warning shouted by the Old Testament prophet Jeremiah that we must repent, and quickly, before all our cities are returned to dust.

A view of Earth rising above the lunar horizon photographed from the Apollo 10 Lunar Module, looking west in the direction of travel. The Lunar Module at the time the picture was taken was located above the lunar farside highlands at approximately 105 degrees east longitude. May, 1969. Photo courtesy of NASA.

But what, I thought as I scuffed at the mold with the heel of my boot in a half-hearted attempt to arrest its growth, what about the others, those who trace their ancestry back along paths other than the patrilineal lines of authoritative Great Men? Ever since I became a parent and a cancer survivor both in the same year, I’ve been thinking less about heroes and their heroics—the Elon Musks who promise to fly us all to Mars, leaving our mess behind, or the E.O. Wilsons who demand that we sacrifice the territory of half the world’s human population (usually the darker-skinned, poorer half) to conservation parks—and much more about caregiving for the damaged, the vulnerable living, the sick.

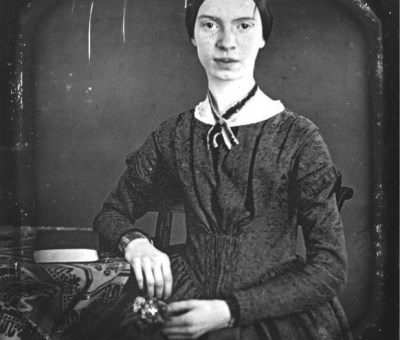

Whenever I start down this trail, I inevitably wind up standing in front of a fat collection of Emily Dickinson’s poems whose place on my bookcase is conspicuous for its lack of dust. Dickinson was famous in her own time for her oddness—as early as the 1850s, when she was in her mid-20s, she began secluding herself within her family home. Eventually, she would only communicate with outsiders through a locked door, and nearly everyone, to Dickinson, was an outsider—she had almost completely withdrawn from the world. Almost. For even though she lived the life of an isolatoe, she wrote: she wrote some of the nineteenth-century US’s most startlingly original poems; she wrote poems that have delighted and soothed and lent solace; she wrote because she could never quite give the terrible world up.

Dickinson’s life seems to have been driven by successive, concussive experiences of loved ones’ deaths—thefts that stole the ground from under her feet, leaving her marooned in a directionless present, and her poems often tremble with a cascading sense of loss. My favorite begins:

I had a guinea golden –

I lost it in the sand –

And tho’ the sum was simple

And pounds were in the land –

Still, had it such a value

Unto my frugal eye –

That when I could not find it –

I sat me down to sigh.

and continues through the vanishing of her favorite spring-time bird, the robin, to the missing of a Pleiad, one of the seven daughters born to the titan Atlas and for whom the seven-star constellation Pleiades is named.1 The guinea, and the robin, and the star all stand in for “a missing friend” whose return is beyond hope. It’s a lonelier world whose outlines Dickinson traces, a poorer, darker, quieter one for which she offers no solutions.

But though her poetry wobbles on the edge of despair, it’s kept upright by what Rachel Carson would pinpoint as the genius of every living thing, “the obligation to endure,” and Dickinson’s poems are marked as much by a vibrant, durable, even defiant ethic of care as by the presence of loss.2 Perhaps paradoxically, the key to her defiance is acceptance. Her poems accept the pain and the loss that each day’s passing washed upon Dickinson’s doorstep. They accept finitude and decay and death. They accept sorrow. Which is another way of saying that they accept life. Dickinson, the shut-in, couldn’t help but to reach out, not with solutions, but in order to cultivate a community through rhythm and rhyme (every poem needs a reader, and every reader a text), to send the evergreen beauty of her spare poetry out into a maelstrom of depression and anxiety, where, one terrible day, not long after I, with my first child on the way, learned that I had cancer, a particular poem, beginning “I had a guinea golden,” alighted on my desk.

Dickinson is no authority. She won’t lead us anywhere, and she promises us nothing. Her poems can’t solve the Anthropocene, and she’s no match for either Prometheus or Jeremiah, both of whom would shush her out of their way. But what Dickinson offers is something humble and everyday and therefore extraordinary in a world looking to authority: care. Her carefully crafted words offer themselves up to us, and it’s no accident that much of her work is rooted in nature, in guineas in the sand, in birds and stars. When Dickinson turns from loss, her chosen metaphor is often something small, delicate, stubbornly alive:

We should not mind so small a flower—

Except it quiet bring

Our little garden that we lost

back to the Lawn again.3

In the late-1950s, the thinker Hannah Arendt wrote an intellectual history of modern times—of what, fifty years later, would be called the Anthropocene. She began with Sputnik, and spun the Soviet satellite into a beeping metaphor for the long-professed, only then recently realized desire to triumph over nature’s fundamental laws. Never before had anything human broken the bonds of gravity to live amongst the heavens. But instead of liberation, Arendt’s history is one of nearly relentless impoverishment, of alienation both from the world and from one another. In her telling, care nearly perished in the modern rush toward the scientific and technological transmission of capital. Nearly, because as she brings her work to a close, she writes of “the miracle that saves the world”: natality—the birth of something new.4

Arendt, like Dickson, like Carson, remained childless, and her natality has little to do with diapers and breast milk and everything to do with delivering into the world new, startling thought, with cultivating and nurturing ideas, and bringing them into a society of caring, careful humans. Thought, writes Arendt, is what makes us human, and thinking a means not only of sustaining our humanity, but also of the capacity to care for one another and for our world. Thought, when cared for, becomes immortal. When I read Arendt, now long dead, I think backwards to Dickinson, and I wonder: how would the story of the Anthropocene unfold if told as a tale not only of catastrophe, much less of conquest, but of care?

Dickinson, of course, came with me to Madison, and to the nicest office I am ever likely to have once had—three giant, sun-filled windows looked out from the third floor on a glorious stone Presbyterian Church. I had an air conditioner, a closet—there was even a fireplace—and I had it all to myself. But I missed my narrow, shared-three-ways, excuse-me-while-I-scoot-past-you basement office back in Ithaca, with its cranky heat, its ground level window that let in more dirt than sun, and its mildew. It may have been only a grad-student office, but it was the birthplace of my dissertation, my first academic articles, and a few essays. It was home to scores of books, and housed hundreds of now-forgotten ideas. I loved that I worked in a town once loved by my grandmother. I loved that I walked, every day, past the Episcopal church whose brilliant young organist, back in the 40s, one day caught her eye.

Ithaca’s winters are no longer all that cold, and my grandmother died a few months after I moved to the Midwest. I suppose my todays ought to bear little resemblance to all the yesterdays that came before. Except that Dickinson still speaks to me. As does Arendt. And also Carson: “‘The control of nature,’” she famously wrote, with words aimed straight at Prometheus, “is a phrase conceived in arrogance, born of the Neanderthal age of biology and philosophy, when it was supposed that nature exists for the convenience of man.”5 Their voices join those of countless other writers and thinkers, some still living, some long gone, but all part of a community linked through time and past death by nothing more than simple black words on a white page and the faith that, on the other side of the cover, caring hands await.

The radical ecofeminist philosopher Val Plumwood, who spent her life tending to a philosophy centered on care, wrote that, if we’re to make the earth a just home for all living things, we need to change the master story of human history.6 Or perhaps there’s another path. Perhaps we need to search for ways of telling stories other than those of the heroic masters. If I could put my ear to Emily Dickinson’s door and ask her to whisper me the tale of the Anthropocene, I’m not sure what she’d say. But I believe it would begin:

It’s all I have to bring today—

This, and my heart beside—

This, and my heart, and all the fields—

And all the meadows wide—

Be sure you count—should I forget

Some one the sum could tell—

This, and my heart, and all the Bees

Which in the Clover dwell.7

Featured Image: Emily Dickinson, c. 1848. Photographic print of a Daguerreotype. Todd-Bingham picture collection, 1837-1966 (inclusive). Manuscripts & Archives, Yale University.

Daegan Miller is a writer and historian of nineteenth-century American landscapes. He received his PhD in American history from Cornell University, and was an A.W. Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in the Humanities at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His work has appeared in a variety of venues, from creative writing magazines to academic journals, and his first book, Witness Tree: Essays in Landscape and Dissent from the Nineteenth-Century United States is forthcoming from the University of Chicago Press. Website. Contact.

Emily Dickinson, The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson, Thomas H. Johnson, ed., (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1960), 16-17. ↩

“The Obligation to Endure” is the title of the second chapter of Rachel Carson’s, Silent Spring (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1962), 5-13. ↩

Dickinson, The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson, 42. ↩

Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition, 2nd ed. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1998), 247. ↩

Carson, Silent Spring, 297. ↩

Val Plumwood, Feminism and the Mastery of Nature (London: Routledge, 1993), 190-196. ↩

Dickinson, The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson, 18-19. ↩

Bravo! from a U-W Madison English Professor who threw her Full Professorship out of the window when her colleagues became convinced that nature (and self, and soul, and reality, and meaningful action) were all constructions. A terrific, heartfelt brilliant connection between Emily Dickinson and issues of our Anthropocene era. Here’s to the future of literary criticism devoted to these topics – eco-criticism?

Hi, Annis:

Thanks so much for reading the essay, and for your response. I’m raising my glass to you right now, and offering up, alongside your toast, a hearty “here’s to everyone who writes and thinks!”