A Syllabus for Contextualizing Energy Policy Debates

A major consequence of the 2016 U.S. presidential election appears to be the direction of the nation’s energy policy.

A screenshot of “An America First Energy Plan,” taken January 27, 2017 from the White House website.

President Donald Trump’s “America First Energy Plan,” posted on the White House website immediately after his inauguration, stipulates that, to liberate Americans “from dependence on foreign oil,” energy policy will embrace “domestic energy reserves,” “the shale oil and gas revolution,” and “clean coal technology,” among other proposals. It contrasts sharply with the Obama Administration’s now-archived “Climate and Energy” page.

Here we follow the examples of other scholars who have contributed to public conversation by creating accessible syllabi (for example, the University of Minnesota’s brand-new #ImmigrationSyllabus) that compile academic and non-academic readings to contextualize contemporary debates.

Our “America First Energy Plan” Syllabus suggests that we cannot understand current climate and energy debates without thinking historically. Drawing on historian Paul Sabin’s 2010 call for historians to engage in climate change and energy debates, we suggest that discussions of the Trump Administration’s energy proposals would be enlivened by exploring how, in Sabin’s words, “our energy system embodies political power and social values as much as the latest engineering and science.”

As the Administration implements its “America First Energy Plan,” we hope readers will find the sources below useful for understanding the history of American energy and the stakes of current policy.

What illuminating work have we overlooked? We welcome suggestions for additions in the comments.

Unit One: Energy and the Making of Modern America

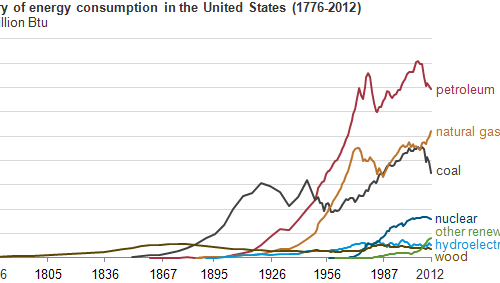

Over the past century, as energy-intensive consumer technologies such as electric lighting, cars, and refrigerators became a daily feature in American life, our energy consumption has increased exponentially, with implications for household economics as well as local and national development, labor, and the environment.

Essential Question: How has energy use, infrastructure, and policy shaped main currents in U.S. history?

- Thomas Andrews, Killing for Coal: America’s Deadliest Labor War (Harvard University Press, 2010). Watch Andrews discuss his book in a talk at the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.

- Brian Black, “Oil for Living: Petroleum and American Conspicuous Consumption,” Journal of American History (June 2012).

- Center for Culture, History, and Environment (CHE), A Primer on Energy (2010).

- Christopher Jones, “The British Shaping of America’s First Fossil Fuel Transition,” RCC Perspectives: Transformations in Environment and Society 5 (2014).

- Martin V. Melosi & Joseph A. Pratt, eds., Energy Metropolis: An Environmental History of Houston and the Gulf Coast (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2007).

- David Nye, Consuming Power: A Social History of American Energies (MIT Press, 1999).

- Catherine Winter, “Power and Smoke: A Nation Built on Coal” American RadioWorks (2011).

President Jimmy Carter signs the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act, August 3, 1977. Photo by White House staff photographer.

Unit Two: Regulation and Its Discontents

The United States, throughout much of the twentieth century, saw repeated bursts of government regulation of the extraction, combustion, and consumption of fossil fuels, from turn-of-the-century municipal anti-coal smoke ordinances to the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act that President Jimmy Carter signed in 1977, near the end of the “Environmental Decade.” Opposition developed among many groups—industry, land owners, proponents of free markets—and became ascendant with the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980.

Essential Question: How have the politics of regulation and deregulation played out in the post-WWII United States?

- Brian Allen Drake, Loving Nature, Fearing the State: Environmentalism and Antigovernment Politics before Reagan (University of Washington Press, 2013). Listen to the Edge Effects interview with Drake.

- Martha Derthick & Paul J. Quirk, The Politics of Deregulation (Brookings Institution Press, 1985).

- J. Brooks Flippen, Nixon and the Environment (University of New Mexico Press, 2000).

- Kim Phillips-Fein, Invisible Hands: The Making of the Conservative Movement from the New Deal to Reagan (W. W. Norton, 2009). View a C-SPAN interview with Phillips-Fein.

- Richard J. Pierce, Jr., “The Past, Present, and Future of Energy Regulation,” GW Law Faculty Publications (2010).

- Paul Sabin, “The Decline of Republican Environmentalism,” Boston Globe, August 31, 2014.

- David Stradling, Smokestacks and Progressives: Environmentalists, Engineers, and Air Quality in America, 1881-1951 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002).

Current and prospective sites of shale natural gas extraction. Map by the U.S. Energy Information Administration, June 2016.

Unit Three: The Fuel Under Our Feet

From the forests of colonial New England to the uranium mines of the Navajo Nation, domestic energy sources have been viewed as one of the greatest advantages of “Nature’s Nation.” But these resources are disproportionately found in the American west, where the federal government in several states manages over half of the land, leading to political debates about what is the best (or “wisest”) use of these places.

Essential Question: In what ways have U.S. domestic energy resources shaped debates about federalism and public lands?

- Andrew Needham, Power Lines: Phoenix and the Making of the Modern Southwest (Princeton University Press, 2014). Listen to an interview with Needham on the “Who Makes Cents?” podcast.

- Christopher Jones, Routes of Power: Energy and Modern America (Harvard University Press, 2014). Listen to an interview with Jones on NPR.

- Patty Limerick, “Hydraulic Fracturing and the Depths of the Humanities,” a public lecture at the University of Wyoming, October 30, 2013.

- Peter A. Shulman, Coal & Empire: The Birth of Energy Security in Industrial America (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015).

- Richard White, “It’s Your Misfortune and None of My Own”: A New History of the American West (University of Oklahoma Press, 1991).

Veteran miner Harold Stanley, right, talks to a young miner who has come into this Richlands, Virginia, mine for the first time. Photo by Jack Corn, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, April 1974.

Unit Four: The Riddle of “Clean Coal”

“The Trump Administration is also committed to clean coal technology…”

Coal is, and has always been, the primary energy source for American electricity. Longstanding concerns about the adverse health impacts of coal dust on miners and the people and wildlife living near mines and power plants have been joined in recent decades by arguments that coal combustion must be halted to mitigate the effects of climate change. The coal industry and research scientists have sought technological remedies for coal’s impacts, and the Mississippi Power Company expected to begin burning coal in the nation’s first large-scale “clean coal” plant today. Critics argue that capturing carbon emissions requires too much energy and that the permanent storage of this captured carbon is unfeasible.

Essential Question: What effects have developments in “clean coal” technologies had on scientific and public debates about responses to climate change?

- Pilita Clark, “Carbon Capture Dogged by Volatile History,” Financial Times, March 27, 2012.

- Richard Conniff, “The Myth of Clean Coal,” Yale Environment 360, June 2, 2008.

- Stephen Chu, “Carbon Capture and Sequestration,” Science, September 25, 2009.

- Dirty Business, directed by Peter Bull (Jigsaw Productions, 2009).

- Barbara Freese, Coal: A Human History (Penguin Books, 2004).

- Michelle Nijhuis, “The Clean Unclean Facts about Coal,” New Yorker, June 4, 2o14.

Unit Five: National Security and the Geopolitics of Oil

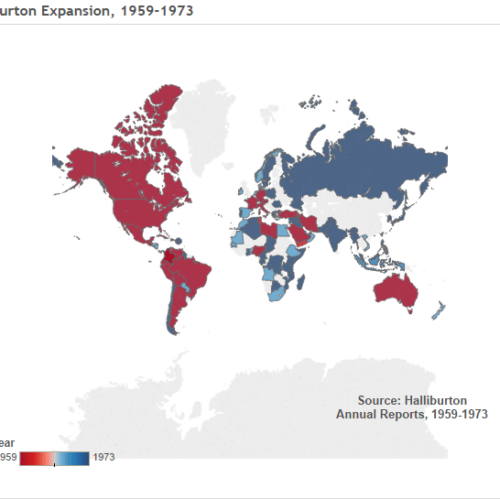

The term “energy independence” entered the lexicon of U.S. politics as a result of the 1973 oil crisis, when the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) cut oil production, leading to a price spike that deepened a recession in the United States. OPEC was retaliating after the U.S. supplied arms to Israel in the Yom Kippur War. Since then, the country of origin of the petroleum the nation consumes has been entangled in both politics and popular imagination with economic and national security concerns.

Essential Question: How has fear of dependence on foreign sources of energy and the rhetoric of energy independence shaped American policy and practice?

- Nathan J. Citano, From Arab Nationalism to OPEC: Eisenhower, King Saʻūd, and the Making of U.S.-Saudi Relations (Indiana University Press, 2002).

- Chelsea Harvey, “Trump Wants ‘Energy Independence.’ We May Already Be Close to Having It,” Washington Post, January 6, 2017.

- Meg Jacobs, Panic at the Pump: The Energy Crisis and the Transformation of American Politics in the 1970s (Hill & Wang, 2016). Listen to an interview with Jacobs on Slate‘s podcast The Gist and read an exchange between Jacobs and Dr. Tyler Priest (University of Iowa) on H-Energy.

- Timothy Mitchell, Carbon Democracy: Political Power in the Age of Oil (Verso, 2011). Watch Mitchell lecture at George Washington University on his book.

- Paul Sabin, “Crisis and Continuity in U.S. Oil Politics, 1965-1980,” Journal of American History (June 2012).

- Robert Vitalis, America’s Kingdom: Mythmaking on the Saudi Oil Frontier (Stanford University Press, 2006).

- Daniel Yergin, The Quest: Energy, Security, and the Remaking of the Modern World (Penguin, 2011). Watch Yergin’s public talk at Yale University.

- Natasha Zaretsky, “Getting the House in Order: The Oil Embargo, Consumption, and the Limits of American Power” in No Direction Home: The American Family and the Fear of National Decline, 1968-1980 (University of North Carolina Press, 2010).

Featured image: A Wisconsin & Southern locomotive passes in front of Madison, Wisconsin’s Blount Generating Station, which switched its primary fuel from from coal to natural gas in 2011. Photo by Rachel Gross.

Rachel Gross is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of History at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her dissertation, “From Buckskin to Gore-Tex: Consumption as a Path to Mastery in Twentieth-Century American Wilderness Recreation,” explores the cultural, intellectual, and environmental history of the outdoor gear industry. She was co-author of “Coal: A Whisper of a Dragonfly’s Wings” for A CHE Primer on Energy. Website. Twitter. Contact.

Brian Hamilton is a doctoral candidate in the Department of History at the University of Wisconsin-Madison writing a dissertation entitled “Cotton’s Keepers: Black Agricultural Expertise in Slavery and Freedom.” He is also the lead author of Gaylord Nelson and Earth Day: The Making of the Modern Environmental Movement and co-wrote the entry “Nuclear Power: Boom and Bust—and Boom Again?” for A CHE Primer on Energy. Twitter. Contact.

You must be logged in to post a comment.