Where the Queer Wild Things Are

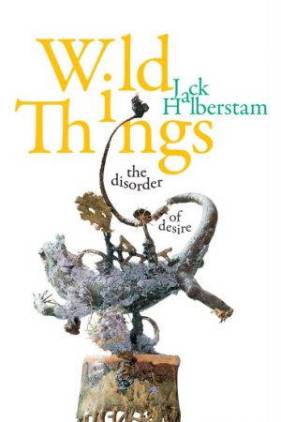

Jack Halberstam, Wild Things: The Disorder of Desire (Duke UP, 2020)

What is “the wild” in the modern era? How do wildness and queerness come together, either in ways that might bolster colonial ideas about who and what is wild or in ways that are decolonial and potentially liberatory? Can wildness be its own way of thinking and knowing? And where should we look to find out? These enormous questions are at the heart of Jack Halberstam’s recent book Wild Things: The Disorder of Desire.

Wildness has historically been a colonial concept, one employed in a “treacherous binary logic” that situates “the wild in opposition to the modern, the civilized, the cultivated, and the real.” This idea of a wild in need of civilizing has justified settler colonialism and other forms of violence and empire. And, as Halberstam writes, “the wild plays a part in most theories of sexuality, and sexuality plays its role in most theories of wildness.” The forms of queerness Halberstam investigates in this book—which often returns to “white male loners” negotiating forms of identity that were “under construction,” inhabiting sexualities that don’t clearly translate into recognizable identities—unfold in relation to understandings of the wild. While there are flashes of decolonial possibility in these archives, the figures Halberstam examines just as often reinforce colonial thinking. Here, queerness and wildness—and their relationship to one another—are ambiguous.

As Halberstam writes, “as much as [Wild Things] is a genealogy for wildness, it also offers an alternative history of sexuality within which the so-called natural world is neither the backdrop for human romance nor the guarantor of normativity. Wildness indeed seeks the unmaking of that world and represents its undoing” as it passes within and beyond “the canon of modernist thought.” Treating wildness as an expansive, raucous concept allows Halberstam to move across canonical writers while also making surprising conceptual leaps to film, TV, visual art, and literature of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

I found chapter 2 of Wild Things most compelling. It exemplifies Halberstam’s wide-ranging analytic mode. The chapter begins with the performance of Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring in Paris in 1913. Composed by Stravinsky with choreography by Vaslav Nijinsky, The Rite departed from the conventions of ballet and musical performance. As the subtitle “Pictures from Pagan Russia in in Two Parts” indicates, the piece brought Parisian audiences an unconventional depiction of supposedly “primitive” rituals celebrating spring. These rituals culminate in the sacrifice of a young girl who dances herself to death.

The performance shocked its audience and was entangled, Halberstam writes, with both “colonial definitions of wildness and . . . a queer version of wildness that jumps genres, breaks loose from history, and reaches for new arrangements of bodies, desire, and temporality.” The chapter takes up the percussive sound of the performance, the awkward movement of bodies on stage, and the audience’s confounded response. Halberstam writes, too, about the loss of the original score and choreography of The Rite, and the ways these losses leave open opportunities for imagining performance in their aftermath.

And yet, this isn’t all. As he parses the forms of wildness The Rite of Spring stages, Halberstam turns to its “legacy of aesthetic wildness,” a legacy that is “both queer, given the collaborative activity that gave birth to it, and decolonial, given the conditions of its rejection in 1913.” Emphasizing the ways Parisian audiences and reviewers derided The Rite as a work of primitive chaos, Halberstam theorizes The Rite’s subsequent cultural impact as evidence that the modern canon could neither successfully incorporate nor fully silence supposedly primitive aesthetic forms. The performance Parisian reviewers scoffed at became one of the most influential pieces of music in the twentieth century.

Following this legacy, Halberstam traces the ways The Rite of Spring reappears in the queer anti-colonial art of contemporary Cree artist Kent Monkman. Monkman’s video installation Dance to the Berdashe (2008) incorporates “a free syncopated version” of The Rite in its performance, in which “the Dandies and Berdashe renew each other’s spirits, thereby refuting their obfuscation by colonial forces.” Halberstam’s chapter ends with an analysis of Monkman’s paintings, in which scenes from colonial histories are recomposed, their content and orientation shifted. Compositions originally organized vertically, as colonial hierarchies, are reorganized to depict a lateral plane of interacting figures. Taken together, Halberstam argues that these works embody an “aesthetic of bewilderment,” marking both the failure of colonial works to subsume and silence Indigenous forms of life and the opportunities for queer reorientations of bodies and spaces.

The expansive arc of chapter 2 is characteristic of Wild Things. The book is divided into two sections. “Part I: Sex in the Wild” focuses primarily on works from the first half of the twentieth century and orients itself in relation to the modernist canon and modern sexology. Within this section, chapter 1 sets up the colonial manifestations of queer desire on which chapter 2’s reading of Stravinsky builds, while chapter 3 reads a set of texts concerning birds to develop an “epistemology of the ferox,” in which desire is defined as an “urgent hunger” enacted across “activities and sensualities not well described by . . . sexual orientation.” The term ferox, which grounds Halberstam’s work here, is Latin for “fierce or wild.” It’s one of several terms Halberstam identifies as associated in some way with the idea of the wild and develops for his critical vocabulary. These chapters examine forms of wildness that collude with colonial power but are also on occasion engaged by Black and Native artists and writers for anti-colonial purposes.

Halberstam works against narratives about disappearing wild life and wild spaces, showing instead the ways wildness is being remade and restaged.

Part II of Wild Things focuses on “Animality.” Departing from the early twentieth-century focus of Part I, Part II extends its analysis across the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. In Part II’s chapters, Halberstam provocatively intervenes in animal studies conversations. Chapter 4 proposes a relationship between the child and the animal and uses wildness to think about the anti-domestic in Where the Wild Things Are and Life of Pi. Chapter 5, the final chapter of the text, links household pets to animals raised for meat, reading these very differently positioned animals as part of a shared form of “zombified” life—a continuum Halberstam argues is also inhabited by the walking dead of popular zombie films and TV shows.

Halberstam casts household pets not as companions in co-evolution in Donna Haraway’s terms but as zombies. This argument counterintuitively stipulates that pets function much more similarly to animals raised for meat than it may seem. Pets, Halberstam contends, are “always already dead in the sense of no longer independent of the humans to which they are now attached, permanently and fatally.” This theorization of zombie animals takes up the human-assisted reproduction required by industrial meat production, the history of bestiality laws, and the affective place of the pet in many American households. These claims stretch the contours of environmental scholarship and thinking about nonhuman life in unexpected ways.

Sailing across an archive so disparate is exciting! But I sometimes wished this were two books, with longer readings of some of the texts Halberstam analyzes and more time to encounter each part’s focus—the connection between colonial and decolonial wildness in the modernist canon and its aftermath (Part I) and animals rendered free, unfree, childlike, or zombified (Part II). Especially for readers who most often think about earlier or different moments of wildness—like me!—Halberstam’s arguments about the wild, the racialized and violently normative category of the “human,” and the ways wildness unfolds alongside the condensation of sexual identities in the modern period give rise to many possible questions about other texts and times. How, for example, could we take Halberstam’s argument about Monkman and the aesthetics of bewilderment as an extension of earlier colonial conflict and decolonial resistance? Although these histories are not Halberstam’s primary focus, he touches on these larger arcs—and I’m eager to think about them further.

Wild Things offers readers and scholars working on environmental questions a vibrant archive for thinking histories of sexuality and desire alongside concepts of the “wild” and its disorders. Halberstam works against public narratives about disappearing wild life and wild spaces, showing instead the ways wildness is being remade and restaged in the early twentieth century and in the present. The text is especially rich as an archive of the ways wildness persists within and can be activated against modernist writers. Halberstam’s wildness is a morally ambivalent, non-identitarian invitation—one that might lead to bewilderment, zombies, children’s books, hawks, or any number of other queer, wild things.

Featured image: Stravinsky Memorial Fountain. Photo by Bill Smith, 2016.

Julia Dauer is an Assistant Professor of English at Saint Mary’s College in Notre Dame, Indiana, where their research and teaching focus on early and nineteenth-century American literature and the environmental humanities. Julia’s most recent contribution to Edge Effects is “Plant Monsters Turn Normal Upside Down,” an essay on the Netflix series Stranger Things (Oct. 2019). Contact.

You must be logged in to post a comment.