Managing the Rights of Nature for Te Awa Tupua

In 2017, the parliamentary declaration of the Whanganui River in Aotearoa New Zealand designated the river Te Awa Tupua to be an “indivisible and living whole.” This language that affirms environmental personhood is a direct translation from an Indigenous Māori cultural expression. A common saying about this river in Te Reo Māori, known throughout Aotearoa, is, “Ko au Te Awa; ko Te Awa ko au,” which means, “I am the River, and the River is me.” The wording of the Whanganui River Claims Settlement casts the “indivisible and living” whole of Te Awa through this cultural framework, and into the legal and administrative apparatus of the state.

Since the Treaty of Waitangi Act of 1975, which established the process of the Waitangi Tribunal in New Zealand, claims like this have been heard in Crown courts for decades. However, Māori negotiators of this particular settlement knew that in this case the formulation of the resolution would be unprecedented for its use of Indigenous language and concepts. This is what sets the Whanganui River declaration apart from other claims settlements based on the Treaty of Waitangi (1840), the foundational document of the nation of New Zealand.

Independent of the national context, international attention has recast the Whanganui River treaty claims settlement as a victory for the “rights of nature.” I learned from those involved that it came as something of a surprise when international journalists first started to ring up from all over the world, inquiring about the declaration. A Waitangi treaty claims case would have neither legal application nor standing outside of Aotearoa. However, this is rarely mentioned outside of New Zealand in celebratory reports and messaging about the river’s newly-recognized “rights.”

Locating Te Awa Tupua in the “Rights of Nature” Discussion

As a legal resident of Aotearoa New Zealand, I tend primarily to view this as a treaty claims settlement, as do most other New Zealanders with whom I have spoken. It is quite a significant one, given that it relates to the great Whanganui River (Te Awa Tupua), commonly called just “Te Awa” (The River). At the same time, as a scholar of environmental humanities in the US, I also am keenly aware that advocates for the “rights of nature” all over the world, however understood, now almost invariably include the Whanganui River declaration of 2017 in lists of examples of global progress in promoting their cause.

The concept of “rights of nature” is advanced worldwide as a legal mechanism often in order that groups may be empowered to care for natural objects, for the well-being of environments and humans (since communities would be empowered to the degree that these objects have legal standing). The invocation of “rights of nature” as a rhetorical slogan in contemporary politics and as a philosophical concept in academic analysis, however, may alter Indigenous, local, and national meanings around environmental personhood.

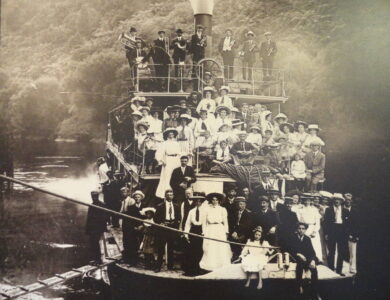

Te Awa Tupua was a main artery connecting Aotearoa’s North Island in pre-colonial times and now has multiple uses.

In the period since the Whanganui River Claims Settlement passed, international English-language press has generally incorporated the declaration into two kinds of concepts. First, it is typically compared to other bodies of water claimed to be like “persons” with rights, like the now-famous case of the Ganges and Yamuna Rivers (later overturned by the Supreme Court of India). This may be why New Zealand’s parliamentary declaration initially captured global attention.

In the United States, the New Zealand case appears like another instance of a body of water, and the communities who depend on it, gaining “rights,” such as for protection, self-determination, or redress. For example, recently in 2019 Lake Erie was granted legal standing by way of such rights by the city of Toledo in Ohio (also with ongoing legal challenges at the time of writing). Just weeks ago, the Yurok Tribal Council voted for rights for the Klamath River in California. There have also been attempts, unsuccessful to date, to achieve legal rights for Lake Superior and the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers, as well as the Colorado River. Rhetorically, these have been hailed as efforts to realize the “rights of nature,” although it is widely recognized that it is local and ancestral communities who rely on the water bodies in the cases above that are the ones directly empowered on their behalf.

Second, irrespective of the kind of natural object concerned, the recent declaration in Aotearoa New Zealand has been popularly hailed as a victory for a universal principle called the “rights of nature.” Evidence of the international advance of this ideal is commonly cited as being the addition or inclusion of principles implicitly or explicitly recognized as “rights of nature” within the constitutions of nation-states, such as those of Ecuador. Many other nations are listed as possibly belonging on the same list now or sometime in the future, from Slovenia (which guaranteed right to water in 2016) to Uganda and Nepal.

The spread of the “rights of nature” concept is often attached to campaigns on behalf of specific environmental objects, such as a current Australian initiative for conservation of the Great Barrier Reef. In North America, these laws are often initiated by Indigenous advocates, sometimes under tribal jurisdiction; an example of this is the case of Manoomin wild rice, traditional food source of Anishinaabeg people in the upper Midwest region of the US, for which both the 1855 Treaty Authority and the White Earth Band of Ojibwe passed resolutions in 2019. In the case of Native nations, achieving recognized environmental personhood, tribal lifeways, sovereignty, and affirming legal and constitutional rights for nature and community may blend fluidly. For example, in 2018 the Ho-Chunk nation, on whose ancestral lands CHE is located at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, added an amendment for the rights of nature to its constitution. This was framed in public messaging in terms of protection from extractive industry practices, such as in the numerous cases of planned mines and pipelines in the upper Midwest that impact native communities. The constitutional amendment was viewed in Wisconsin and watched internationally in connection to a statewide effort and legislative bill in 2018 to protect burial mounds and ancestral sacred sites from proposed mining exploration, as in a previous bill introduced into the state legislature in 2016.

Context shows how rights and personhood combine in social life and environmental practice.

From the popular and academic perspective of environmental law and ethics, a “rights of nature” discourse can readily elide a language of personhood and of rights without grounded consideration of further or unique cultural, political or historical circumstances. Features of Anglo-American law afford standing on the basis of recognized personhood (such as for a fetus, or a corporation, in other areas of discussion in the current legal landscape of the USA), and the granting of nature’s rights hinges on affording a natural object or environmental entity standing with respect to established norms like property law. Advocacy groups see this as a mechanism to empower the communities who would be designated as environmental guardians. The proposition of environmental rights along these lines was famously worked out as a thought experiment by Christopher Stone, based on answering a hypothetical question posed by a law student in class, in his 1972 book, Should Trees Have Standing. Now 50 years later, tangible initiatives and legislation are promoted in the US and countries elsewhere by organizations like the Earth Law Center and the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund.

From the perspective of environmental humanities, personhood and rights frequently come together as the central story of environmental ethics in white-settler tradition, such as in widely-used undergraduate textbooks in Environmental Studies that present universal “environmental ethics” as a process of extending increased acknowledgment across classes of humans, nonhumans, and non-sentients. For example, Roderick Nash recounted the history of environmental ethics in these terms in the now-classic book, The Rights of Nature: A History of Environmental Ethics (1989). Animal rights is a key part of this story in theory and practice as was Aldo Leopold’s land ethic.

In the case of the Te Awa Tupua settlement, the direct translation from the language Te Reo Māori gave unique expression to a Waitangi treaty claim. The framework into which it fit—treaty claims—was not altered by this language. It was not intended to be a “rights of nature” resolution, even by those who rendered the Indigenous language into English for the law of the state. However, if this is to be received as an achievement of the rights of nature, whether in Aotearoa or elsewhere—and it already is considered to be so elsewhere—here is another process of translation to consider.

Context shows how rights and personhood combine in social life and environmental practice and meaning, in Aotearoa, and also elsewhere. The ambiguity of the declaration of 2017 in theory and in practice means that it is only through implementation that the questions of rights, responsibilities, and personhood will be worked out, ontologically, ethically, juridically, and financially. In early 2018, I travelled back to Aotearoa with this in mind. I visited the new office charged with making sense of the declaration and enacting it. Is it through management that the letter and the spirit of the legal treaty claims settlement, and the meaning of “rights of nature,” becomes both present and real.

Click images to enlarge.

Understanding Environmental Personhood through Management

Nationally and internationally, Te Awa is a major recreation destination, representing the nation of New Zealand’s reputation for natural beauty and outdoor experience and adventure. Some reactions to the declaration in 2017 and 2018 voiced by pakeha New Zealanders, such as in print, expressed anxieties about what could happen to change access. Māori leadership has had no plans for any such changes, as they have expressed publicly many times.

When I spoke to one Māori leader and advocate about this, I was told, “We just want to care for our river.” To begin to understand what the personhood or rights of the river means, symbolically or materially, and both inside and outside of frameworks meaningful in Aotearoa New Zealand, requires understanding the management of Te Awa and the terms of this care, in both theory and practice.

The declaration of 2017, as a settlement based on the Treaty of Waitangi (1840), is one of two treaty claims about the river and surrounding land that were put in process in recent years. The land claim was still pending in 2018. Like all claims settlements based on the treaty, the Whanganui river declaration stipulates financial redress, an apology from the Crown, and cultural association with the site. While received internationally as an advance for environmental conservation, most of the document of the treaty claims settlement bill does not concern the river per se, but the communities who care for Te Awa, such as by outlining the structures by which the Ngāti Hau, numerous iwi (tribes), will determine how to undertake environmental and financial management of the river.

The framing language of the document is unusual and underscores the connection of environmental rights and personhood that has captured international attention in this case. The declaration translates Indigenous language and reads, more fully: “Te Awa Tupua is an indivisible and living whole, comprising the Whanganui River from the mountains to the sea, incorporating all its physical and metaphysical elements.”

The office of the agency, Ngā Tāngata Tiaki, responsible for managing the river after the settlement.

Under the declaration, a new agency, Ngā Tāngata Tiaki, has been charged with the implementation of the settlement. I visited the office in the months just as it was first being set up. Outreach to the iwi is a big process, and these conversations and negotiations are the focus of much of the first stages of implementing the settlement. Another priority at the time of my visit was to contract and complete the required environmental impact studies and scientific evaluation.

Beyond this, immediate issues of management are at the boundaries of understanding how the settlement shapes the rights and personhood of the river as now officially recognized by the state. Many of these questions relate to the boundary of what constitutes Te Awa, in the declaration’s language, as an “indivisible whole,” incorporating “physical and metaphysical elements,” and even extending “from the mountains to the sea.” For example, there are concessions for water and gravel extraction that precede the declaration, and with leases that extend into the future. In addition, leaders were asking wider questions as well, such as how would the standing of the river in terms of “personhood” translate in terms of responsibilities as well as rights? Below are three kinds of issues that show how management shapes what would be cast as the salient contours of “rights of nature” in this context.

First, at Ngā Tāngata Tiaki there was the question of co-management with the Department of Conservation (DOC) in the river’s upper region. There are a series of huts, the area around which the iwi would be responsible. What are the expectations of maintenance, liability, and so forth, and what does this mean in partnership with the DOC? For example, if the DOC maintains the huts for paddlers, how then is access from the huts to and from the river to be managed?

A second area of concern relates ancestral and cultural sites. Māori residents with whom I met along the river shared their anticipation of eel fishing, and restoring traditional platforms along the river bank in order to do so. However, the unseen dimensions of ancestral sites pose a greater challenge. At the time of my visit, for example, protection of “metaphysical” sites and customs was a rationale given for advancing a proposal for management on nearby Mount Taranaki, announced just when I happened first to arrive in Whanganui city. (Within days, international coverage already had translated this into a language of the “rights of nature.”) On Taranaki, I was told by Māori leaders in the region, there had been numerous problems with public visitors, such as to Egmont National Park. Scattering the cremated ashes of deceased persons in the landscape was a serious, ongoing issue, for example. Human remains make an area unusable for weeks following Māori cultural norms. In addition, on and around Taranaki, as along Te Awa Tupua, many of the most important sites and features that are “physical and metaphysical” are not marked; how to maintain them properly while not making them conspicuous (and thus even more vulnerable) is a challenge here as it is worldwide.

An historical site along the river. Maintaining these important sites properly while not making them conspicuous (and more vulnerable) is a challenge.

Third, claiming that Te Awa extends “from the mountains to the sea” heightens the ambiguity about how to understand its parts with respect to its “indivisible whole.” For example, the river flows through the center of the city of Whanganui. At the time of my visit, there was a national proposal pending to build a new major port on the North Island at Whanganui. An immediate question on the part of the project’s stakeholders and others was, how would the iwi work with the authorities on this potential project at the mouth of the river?

In addition to matters like the three points above, if the river has “rights” like a person, it may also have responsibilities (a point also mentioned by Stone in his book half a century ago). The Whanganui River commonly floods along its lower stretches, and under the principle of the settlement “the river” might now actually be held liable for damages in an event or circumstances like this. Similarly, where the river meets the ocean there is a residential area called Castlecliff, a community built largely on coastal sedimentary ground that would be unstable in the event of an earthquake. Earthquakes are extremely frequent in New Zealand. Are the iwi responsible for this area and its residents since this, too, is part of Te Awa?

Te Awa Tupua flows through the major city of Whanganui, creating a complex set of issues for river management as infrastructure expands.

While these issues will be resolved in Whanganui, and Aotearoa, they point out how the meaning of rights of nature and environmental personhood is embedded within management theory and practices. Outside of Aotearoa in 2019, Te Awa Tupua, Mount Taranaki (as discussed above), and the 2014 declaration of the management of Te Urewera National Park by the iwi Ngāi Tūhoe on the North Island (fully implemented in 2018) are all three frequently claimed to represent the progress of an international global “rights of nature” movement. However, just these three recent cases are all independent of one another, and differ greatly in legal process and status, such as with respect to Waitangi treaty claims. Looking even more closely across these cases, management structures present significant qualitative differences to analyze against the background of environmental personhood. Scholars in New Zealand, for example, have pointed out how different the management model of Te Awa Tupua is from Te Urewera National Park.

This case from 2017 of the Whanganui River declaration, and early efforts at the implementation of this Waitangi treaty claims settlement in 2018, show that whatever it is that the “rights of nature” means for such a case transpires through management. Theorizing a local, national, or universal rights of nature means looking to human-environment interactions of management like infrastructure development, flood and disaster planning, balancing conservation and recreational use, and the limits of extractive industry practices. Whether the academic explanation of “rights of nature” outside of Aotearoa will have the conceptual tools to compare New Zealand cases, much less transnational ones, will depend largely on how much that analysis can shift away from the colonial heritage of “rights” and “nature”—even as it works within systems of Anglophone law as in the US and New Zealand—and appreciate the lived realities of management in relation to environmental personhood. These management practices embody meanings of the rhetorical expression of “rights of nature” in a global context; and for Aotearoa, caring for Te Awa Tupua represents what the expression, “I am the River, and the River is me,” means for the nation.

Editor’s note: All photographs included are by the author, 2018.

Anna M. Gade is Vilas Distinguished Achievement Professor in the Gaylord Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies at University of Wisconsin–Madison, where she teaches Environmental Humanities, and is a Center for Culture, History, and Environment (CHE) faculty affiliate. Her previous position was in the Religious Studies Programme at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. This post is based on a presentation to the Coming Together of Peoples Conference sponsored by Indigenous Law at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in Spring 2018 and a colloquium presentation to CHE in Fall 2018. Her most recent book is Muslim Environmentalisms: Religious and Social Foundations (Columbia University Press, 2019). Website. Contact.

You must be logged in to post a comment.