Memorializing Wildfire at the Playground

This essay explores the politics of wildfire memorials and environmental monuments in our rapidly changing climate. It is part of the Troubling Time series, which interrogates environmental ideas, spaces, processes, and problems through the lens of temporality. Series editors: Rebecca Laurent, Rudy Molinek, Samm Newton, Prerna Rana, and Weishun Lu.

“A monster’s coming,” my son, Adrian, whispers, his wide eyes looking up at me in earnest. “Oh no!” I reply. We lean our backs against the sloping wood of one side of the tall sculpture, finding a hiding spot in the middle of what looks like a fire-struck tree trunk. Adrian looks furtively across the park lawn to a playground where kids shriek with delight from the top of the slides. It’s a perfect sunny afternoon, and the sculpture casts sharp shadows on the pavement. While Adrian keeps an eye out for monsters, I shrug off the sense of unease that always returns when we play here, in the neighborhood’s wildfire memorial.

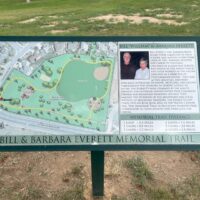

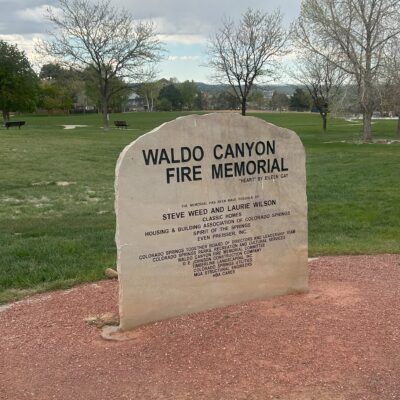

Heart, a 2014 sculpture by Eileen Gay, looks over the juncture of several walking paths in Mountain Shadows Park in Colorado Springs. It was dedicated ten years ago as part of a memorial to the victims of the massive 2012 Waldo Canyon fire. There are other reminders of the fire in the park. The playground is encircled by tiles painted with messages of hope and encouragement (“C’mon trees,” one urges). A bronze cast of a fallen tree trunk functions as a bench for visitors, a gift from the “creators and sponsors” of a local art exhibit a year after the devastation of Waldo Canyon. Atop the log sits a fox that looks knowingly toward the foothills, where the skeletons of charred trees can still be seen, stretching toward the sky.

Danger exists here, but it’s not the kind of shadowy monster that a two-year-old imagines. Rather, it’s the bright light of a tragedy that will return again: the brutal wildfires that threaten the Mountain West, year after year.

Contested Returns

One of the first times I visited the park with my son, an older man passing by remarked, “Kids love this thing,” nodding at the wooden sculpture. If you’ve ever spent time with a toddler, it’s easy to understand why. Embedded in its trunk are a number of brass house keys—perfect for practicing counting—and various other colorful objects, including small glass hearts and beads that we use for “I Spy” games. According to the artist’s statement, these mosaic pieces are intended to symbolize renewal. Notably, the memorial’s major donors include a regional home builder and the city’s House and Building Association.

Rebuilding, though, remains controversial, particularly in the wildland urban interface (also called the WUI), the boundary between residential areas and wildland vegetation, In this vulnerable area, priorities for affordable housing, economic growth, conservation, and wildfire safety are seemingly at odds. Questions concerning the cost and scope of reforestation loom for neighborhoods rebuilt in heart of the burn scar. Thus, inasmuch as the Waldo Canyon Fire Memorial marks a site of healing and return, it also embodies the contradictions and complications the city faces years after the fire’s devastation.

The Waldon Canyon Fire Memorial is one of many. More recent examples include the 2016 Wildfires Memorial and Tribute Plaza in Gatlinburg, Tennessee and Hope Plaza in Paradise, California, a project underway to remember the victims of the devastating 2018 Camp fires. The National Climate Assessment (NCA) predicts that due to climate change, wildfires—particularly in the Mountain West—will increase in frequency and intensity for the next thirty years. A new era of wildfire memorial is coming, though what political project these memorials will serve is not so clear.

Memorials are expensive and challenging to build, and many communities look to corporate donors and other kinds of public-private partnerships to fund them. With different stakeholders at play, the interpretive signs and artistic expressions of these memorials often elide climate change’s role in these fires. The Waldo Canyon Fire Memorial, for example, is seemingly politically neutral in its expression of remembrance. A timeline installed by the park garden begins with the first sighting of smoke in the Rampart Range and ends with a “community reborn.” The ecopolitical realities of the place—the ways that politics and ecology shape its existence—are left out of the memorial’s account of the event, facilitating a mythology of return while leaving the specter of climate change unnamed.

As I’ve returned to the park over the past year, I’ve reflected upon why this omission matters to me. As a newcomer to the area, what relationship do I have to the memorial? Why do I care if it stakes a political position? What am I looking for in this place? The answers, I think, lie in my own feelings of powerlessness as I navigate a warming world that has passed the point of no return, and the ways I have looked to the memorial to mediate these feelings.

Memorials to a Warming World

In her 2012 book Memorial Mania, art historian Erika Doss explores memorials in America through their function as “archives” of public feeling. There are many things we ask of our memorials, which serve as material expressions of loss, shame, anger, and redemption. The Waldo Canyon Fire Memorial’s artwork and walking trail, for example, materialize the community’s trauma, grief, and hope. According to Gay, the sculpture itself “represents an old growth tree, split, blackened and hallowed out by fire yet, as a symbol of its strong heart, still reaching for the sky with anew growth of green.” The memorial signage likens the tree to the community’s determination to “come back, grow, and thrive,” its fixity a trait and virtue of survival.

In contrast to permanent memorials honoring specific people and events (often war-related), however, memorials dedicated to climate change-related phenomena are frequently as ephemeral as the conditions they memorialize. In the world of galleries and museums, temporary displays related to ongoing changes like rising sea levels or species extinction have become common. Recent examples include Maya Lin’s Ghost Forest (2021) and the Umbrellium’s Singing Trees (2020). Lin installed 49 Atlantic white cedars in an area of Madison Square Park, recreating the so-called “ghost forests” that have become familiar due to rising sea levels and other events related to global warming. Singing Trees, a traveling sound installation, highlights the noises and activities of local flora through ambient music representative of the exhibit site. Ghost Forest stood for about six months, while the Paris installation of Singing Trees lasted the duration of COP25. Both projects are examples of short-term installations conveying transience and ephemerality as part of their story of species and habitat loss.

Memorials to “environmental loss” in the age of climate change are, by nature, different from war and conflict-related memorials. As designer-scholar Anita Bakshi writes, “Any efforts to commemorate such losses [such as extinction or environmental degradation] must recognize the ongoing nature and uncertainty of changes that have not reached a clear conclusion point.” Climate change complicates the function of public memorial, in other words, because it interrupts the sense of closure these sites are traditionally meant to provide. For Bakshi, a climate change memorial should not be a place for storing feelings but, rather, a place for transforming them into political action. The pressing question their designers must address, Bakshi contends, is “How can we experience ourselves in larger scales?”

Climate Chronograph, the winning design of the National Park Service’s 2016 “Memorials of the Future” competition, offers another perspective. Different from ephemeral installations or monumental sculptures, Climate Chronograph explores the temporal scale of climate change through “intergenerational time.” The design envisions a small orchard of cherry trees on a plot of land extending into the Potomac River. Visitors would experience an increasingly flooded place as they return throughout their childhood and adulthood.

This “emergent process” differentiates the proposed project from other examples of climate change memorial, as the submersion of the orchard would happen across years and decades. The designers describe this process as “apolitical datum for today’s climate challenges and questions.” Climate Chronograph reminds us that public memorials exist in continuum with natural environments whose own agencies are apolitical.

A new era of wildfire memorial is coming, though what political project these memorials will serve is not so clear.

The ostensible purpose of Climate Chronograph is not to elicit or mediate feelings of grief or anger but instead to “witness” the event of climate change through its materialization. Unlike traditional memorials, Climate Chronograph would document climate change’s present and ongoing destruction of a place, the memorial’s political project strengthened by the affective attachments visitors form with the park over time, as it slowly vanishes.

As I contemplate the meaning of the Waldo Canyon Fire Memorial, I notice its similarities to the “emergent process” proposed by Climate Chronograph. Even if the memorial elides climate change’s role in the fire, the saplings on the canyon in the burn scar visible from the park serve as a material record of the time between past and future conflagrations, making legible the conditions that the memorial itself leaves unnamed. The scar itself both records and remembers. Of course, it is up to visitors to notice.

A Record of Hope

The Waldo Canyon Fire Memorial is a decade old this year. A generation of children has grown up around it. And although more wildfires have come and gone in the area (one as recently as this past spring), the park thrives as a community space. Soccer leagues meet here in the fall and spring, and every December, friends congregate in the cold to watch a Christmas tree lighting. It’s a memorial that makes way for the daily life of a community that, for better or worse, has rebuilt itself in a place startlingly vulnerable to another tragedy. For them, the memorial is meaningful in the continuity it offers, the idea of rebirth and a certain kind of resilience.

As I’ve grown to accept that the memorial doesn’t make the political pleas I desire, I’ve started thinking about the ways I might talk about this place with Adrian as he gets older and the place of play and storytelling within these lessons. I wonder what the park’s monsters might teach us, and how we might learn to live—and play—alongside them, instead of running and hiding. I’ve realized that I don’t need the memorial to imagine possibilities for me; rather, the future is one I need to create with Adrian as he looks for his own sense of purpose in a warming world. The memorial is just one place we can do this work together.

Featured Image: Eileen Gay’s “Heart,” a memorial for the Waldo Canyon Wildfire. Photo courtesy of the author, 2024.

Jessica George is a writer and community college educator. She holds a Ph.D. in English from Indiana University Bloomington. Her scholarship on American literature and the environment has been published in the Journal of the Midwest Modern Language Association and ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment. Contact.

You must be logged in to post a comment.