Snapshots of the Anthropocene in Iran

“No one wants to believe the garden is dying,” starts a poem by the Iranian writer Forugh Farrokhzad, “that its heart has swollen in the heat of this sun, that its mind drains slowly of its memories.”

Farrokhzad, a feminist author writing in the 1950s and 60s, projects psychological decay and cultural erosion onto her family’s garden, a Persian symbol of paradise and divine love. Despite its Persian symbology, she writes, “Our neighbors plant bombs and machine guns, instead of flowers, in their garden soil.” Their garden is dizzy.

Farrokhzad’s vision of a landscape interwoven with political overtones and the quotidian details of daily life resonates with the work of contemporary Iranian environmental photographers. In their photographs, the land becomes a repository for memory and a terrain for projections; it is animated by the rituals and lives of those who inhabit it. The garden, the river, the lake, the salt flat—these unstable terrains are marked by the motions of individuals, of families, of populations. In contemporary Iranian photography, landscapes become living archives of cultural tectonic shifts.

I began to engage with these themes in my research on Mashhad, my father’s hometown in Iran. This area, near the Kashafrud River, has been inhabited for over 800 thousand years. As the riverbed dries due to climatic changes, it exhumes Paleolithic tools. With layers that contain traces of past lives, the river is a geological palimpsest. Memory is often conceived as intangible or abstract, but it is ossified in the marrow of Kashafrud, deposits lodged in rock beds and ice sheets. In the decanted basin, the land itself remembers.

Iranian photographers Ako Salemi, Hashem Shakeri, Hoda Afshar, and Tahmineh Monzavi are helping to document the memory of earth and people across regions often excluded from dominant narratives in Iran. I curated the exhibition Water and Oil, currently on view at the European Cultural Center in Venice, to explore the interplay between environment and identity, peripheral geographies, and erased histories.

Together, these photographers explore the outer limits of memory at a time when the Earth’s present is rapidly changing through ecological collapse, displacement, and biodiversity loss.

The photographers featured in Water and Oil reveal a symbiotic relationship between ecology and history, showing how environmental changes shape local identities. They interrogate what it means to remember. Their endeavor to document the fluctuations, ebbs, and flows of nature is, in a certain sense, an exploration of the medium of photography. Photography itself is also an archive and a repository for memory.

How do you document the memories of the earth? What does the Anthropocene look like? How does one represent a change in the air, the wind? These photographers explore how to represent the unrepresentable: the absence of water, the presence of air, and the feeling of home.

Photographing a Ghost

Iran once possessed one of the largest bodies of water in the Middle East. Lake Urmia, at one time the sixth-largest saline lake in the world, is now mostly desert.

Ako Salemi photographs the desiccation of the lake. He depicts a scarred landscape teetering toward water bankruptcy; stark silhouettes throw suffocating lands into sharp relief. In one image, cracks stretch across the land Lake Urmia used to cover, giving the sense that the water basin is shattering. He also captures the grainy, egg-film texture of the heat.

Salemi also records the mechanisms of these changes. In one of his pictures, a distant oil flare is flickering in the horizon between two sandy mountains on Kharg Island, a hub for oil exports in the Persian Gulf. The unassuming flame that illuminates the center of the image hints at the labyrinth of seismic infrastructures beneath the sandy mountains.

The Desert Left Behind

The Hamun Wetlands are similarly disappearing. Hashem Shakeri’s photography conveys the impact on agricultural workers, 25% of whom have migrated in recent years. In his bleached and flattened photographs of the wide-open desert left behind, Hashem Shakeri captures how the few remaining families cope with the ghost of the lake.

Shakeri’s photos pay special attention to where the botched horizon hugs the rim of the sky. Figures walk or stand before the breadth of a sun-bleached horizon line. In one image, a little girl punctures the center of a vanishing point that is otherwise almost entirely flooded with sharp, white light.

Photographs by Hashem Shakeri, 2018.

His photographs are both portraits and landscape shots. The images are as much studies of individuals as they are studies of their environments. They are somehow microcosmic and macroscopic. They imply that changes in the earth’s texture reverberate in the lives of the individuals photographed.

By focusing on both peripheral spaces and faces from the borderlands, Shakeri shows how diasporic and geological memories are entangled.

The Colors of the Wind

Hoda Afshar’s dreamlike records of the Island of Hormuz and its inhabitants show how intergenerational memories shape interactions with the environment.

Hormuz is a geological treasure trove, often referred to as the Rainbow Island for its cavernous stone formations and glittering, red-stained sea. It is also a commercially and militarily strategic chokepoint from which over twenty percent of the world’s oil is exported.

Photographs by Hoda Afshar, 2015-2020.

The African-Iranian communities that Afshar documents are the descendants of maritime merchants and slaves. Afshar captures their shamanic rituals as U.S. nuclear-powered submarines and oil tankers traverse the Persian Gulf.

The interpenetration of human bodies and natural forces takes center stage in Afshar’s lyrical photographs. Human bodies occupy spaces, but local communities believe that their bodies are, in turn, occupied by ecological forces, like wind. Afshar photographs local, shamanic rituals used to exorcise the winds from an afflicted body. A shaman lures out the wind by uttering poetry and chants in Swahili, Arabic, or Farsi. A body covered in a white cloth dances and thrashes.

Photographs by Hoda Afshar, 2015-2020.

This view of the wind, as both a bodily contagion and a supernatural power capable of carving the surreal stone landscape of Hormuz, upends the nature-culture binary. Their exorcism, for example, attests to the permeability of the human body by ecological forces. The body is porous; it lets the outside in.

The rituals are an example of the communication of “postmemories,” Marianne Hirsch’s term for ancestral memories transmitted from parents to children. These rituals, likely passed on from pearl divers as well as slaves brought by Arabic traders, connect the locals of Hormuz to their forebears, both environmentally and culturally. It is believed that the winds, like the ceremonies, originate from Eastern Africa.

The Picture of Defiance

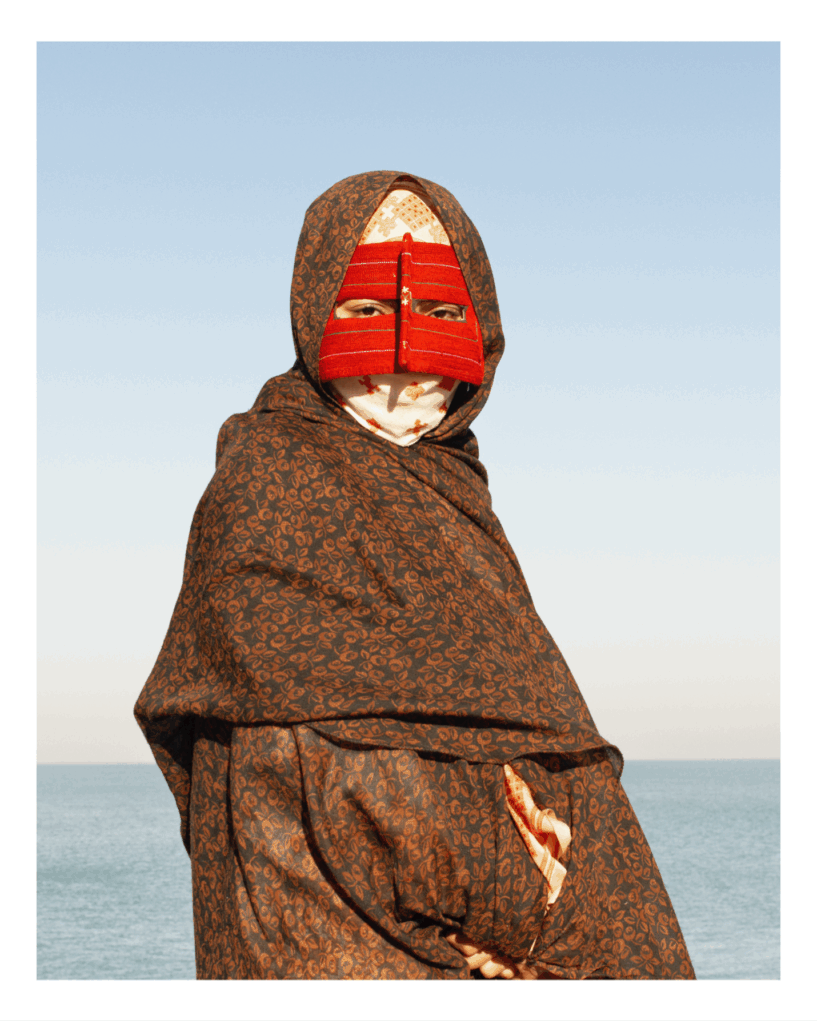

Men generally conduct the rituals that Afshar photographs. Tahmineh Monzavi looks elsewhere. Their series titled the Zangi Women pays special attention to how gender is performed in the African-Iranian communities of Balochistan.

Photographs by Tahmineh Monzavi, 2020-2022.

Monzavi shows women deeply immersed in their atmospheres, projected against the sea or lounging in a slant of sunlight in the grass. The calm figures are quietly poised, at times with their masked gazes fixed on the viewer. The women’s repose upends spatial, and racial, hierarchies. Monzavi records their daily lives, their participation in communal traditions, and the ways they have assimilated into Iranian culture while upholding the rites they’ve inherited.

Diasporic and Geologic Memory

Afshar, Monzavi, and Shakeri capture the entanglement of diasporic and geologic memories by revealing how the politics of migration and exile leave imprints on land. They account for the geographical stores of memory in the landscape, and they pay homage to ecological archives.

Together, these photographers explore the outer limits of memory at a time when the Earth’s present is rapidly changing through ecological collapse, displacement, and biodiversity loss. Their images map a social ecology in which individuals and environments co-constitute one another. While doing so, they capture peripheral spaces and communities long excluded from dominant narratives. By documenting landscapes and populations marked by migration and environmental exploitation, they redefine the boundaries of memory and belonging.

Featured image: A Zangi woman in the desert. Photo by Tahmineh Monzavi, 2020-2022.

Angelica Modabber is a curator and writer based in New York and San Francisco. She completed her Ph.D. at Columbia University.

You must be logged in to post a comment.