Dark Fiction, Sinister Reality: A Conversation with Brenda Becette

This bilingual episode was translated in real time by Sally Perret and in press by Nicolás Felipe Rueda Rey.

Este episodio bilingüe fue traducido en tiempo real por Sally Perret y en prensa por Nicolás Felipe Rueda Rey.

On a spring day in 2025, I had the pleasure of meeting Argentine writer Brenda Becette as part of her visit to University of Wisconsin-Madison’s campus. Although we share different first languages, we exchanged a warm greeting and were able to sit down to record Edge Effects’s first ever bilingual podcast episode. Professors Sarli Mercado and Sally Perret joined us from the 4W Initiative—a campus group dedicated to using education, mutual care, and community to face challenges that women experience. The 4W Women in Translation project inspired this episode, as it aims to use Spanish/English translation to benefit readers around the world.

We discussed Becette’s book, La parte profunda (Editorial Universidad de Guadalajara, 2018), and especially her inspiration for portraying darker themes in environmental and women’s stories. Listeners should enjoy her excerpt reading, which was a favorite part of the experience for me as host. It was wonderful to be part of this incredible conversation, with many thanks again to Perret for her interpretive expertise.

En un día de primavera de 2025 tuve el placer de conversar con la escritora argentina Brenda Becette como parte de su visita al campus de la Universidad de Wisconsin-Madison. Aunque nuestros idiomas son distintos, intercambiamos un afectuoso saludo y grabamos el primer episodio bilingüe del podcast Edge Effects. Las profesoras Sarli Mercado y Sally Perret se sumaron desde la Iniciativa 4W, un grupo del campus dedicado a enfrentar, mediante la educación, el cuidado mutuo y la comunidad, los desafíos que atraviesan las mujeres. El proyecto 4W Women in Translation fue la inspiración de este episodio, ya que busca aprovechar la traducción entre español e inglés para beneficiar a lectoras y lectores de todo el mundo

Conversamos sobre el libro de Becette, La parte profunda (Editorial Universidad de Guadalajara, 2018), y especialmente sobre la inspiración para abordar temas más oscuros en las historias sobre el medioambiente y las mujeres. Quienes escuchen el episodio podrán disfrutar de su lectura de un fragmento. Para mí como anfitrióna, una de las partes más valiosas de la experiencia. Fue maravilloso ser parte de esta increible conversación. Un agradecimiento especial a Perret por su pericia interpretativa.

Stream or download our episode here.

Pueden escuchar o descargar el episodio aquí.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Spotify | TuneIn | RSS

Interview Highlights

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Esta entrevista ha sido editada para mayor brevedad y claridad.

Bri Meyer: In La parte profunda, your stories tend to highlight the uncanny, or more sinister, themes of human nature, making them very pronounced. How do you use fiction to connect to the human tendency for self-destruction and the human tendency for environmental destruction?

En La parte profunda, tus historias tienden a resaltar los temas inquietantes, o más siniestros, de la naturaleza humana, haciéndolos muy evidentes. ¿Cómo utilizas la ficción para conectar con la tendencia humana a la autodestrucción y a la destrucción del medio ambiente?

Brenda Becette: En realidad, esa extrañeza ya estaba en el aire en la época en que escribí estos libros, y era algo de lo que hablábamos también con otros escritores. Y si uno va a estar en el mundo del arte, es clave mantenerse al tanto de lo que pasa y tener la sensibilidad para captar los acontecimientos. No es que intentáramos ser ministros ni magos, pero veíamos que las cosas estaban a punto de estallar. Se volvió tan evidente y fue más allá de todo lo que podíamos imaginar a medida que seguía avanzando. Por eso, incluso los cuentos de este libro, que me parecían distópicos, en realidad no están tan lejos de lo que ocurre en mi país y en otros, acá y en Europa.

Es muy loco. En particular, El cuento de la criada yo pensaba que era fantasía, y ahora veo grupos que intentan impulsar esos modos de vida. Sobre todo para las mujeres, da la sensación de que estamos retrocediendo a ideas que buscan reinstalar estructuras sociales del siglo XIX sobre cómo se supone que debemos ser, tanto en mi país como en todas partes.

Como diría Kafka, un libro tiene que ser el hacha que rompa el mar helado que tenemos dentro, algo que quiebre esta paz extraña.

En verdad, lo que necesitamos es frenar. En mi país se dice que tenemos que dejar de querer producir industria y que se quiere volver a ser el granero del mundo, el proveedor de carne y granos de los países que antes considerábamos colonia. Como si ése fuera nuestro único papel. Es una locura, y todo parece estarse volviendo realidad: cosas que antes eran pura ficción.

In reality, this kind of strangeness was already in the air, and it was something that other writers were talking about. And if you’re going to be in the art world, it’s really important to keep up with what’s going on and to feel current events. It’s not like we’re trying to be ministers or Magi, but we saw that things were about to explode. It became so evident and went beyond anything that we could imagine. So even these stories that seem dystopic, they’re not so far from what’s happening in my country and in others here and in Europe.

As Kafka would say, art is the axe that breaks the frozen sea within us, something that shatters this strange peace.

It is crazy. I thought The Handmaid’s Tale in particular was fantasy, and now I see groups trying to promote those ways of life. It feels like we’re going back to nineteenth century ideas of how women are supposed to be, in my country and everywhere.

Really, what we need to do is stop. In my country, people say we have to stop trying to produce industry and that we want to return to being the world’s breadbasket, the supplier of meat and grain to the countries we once considered colonies, that this is our only role. It’s crazy. Everything happening now used to be fiction.

BM: Many of your stories are narrated by women. Was this a conscious choice? Why did you choose to do this?

Muchas de tus historias son narradas por mujeres. ¿Fue una decisión consciente? ¿Por qué lo hiciste?

BB: Bueno, no es una elección consciente escribir desde el lugar de una mujer, sino más bien una especie de pulsión por escribir desde los lugares atacados, desde quienes tienen que luchar o defenderse: las mujeres, los niños y el medio ambiente. Es una forma de respuesta o —si me voy más lejos— de venganza. Alguien tiene que defenderlos. Es, en definitiva, una respuesta a la violencia ejercida desde el poder.

It’s not necessarily a conscious choice to write from the place of a woman, but it more comes from an impulse to write from a place of those that are attacked constantly: women, children, and, of course, the environment. It’s my way to answer, to respond with a little bit of revenge or vengeance. Because someone has to defend it; someone has to defend nature, our resources, and all the people that don’t have access to power.

BM: We recently published a Faculty Favorites article on the theme of environmental activism in art and fiction. Connecting to that theme with this podcast, I’m curious how you think your readers will perceive the darker human and environmental issues that you explore in your short stories. What kind of action or reflection would you’d like to spark with your writing?

Recientemente publicamos un artículo en Faculty Favorites sobre el activismo ambiental en el arte y la ficción. En relación con este podcast, me interesa saber cómo crees que tus lectores percibirán los problemas humanos y ambientales más oscuros que exploras en tus cuentos. ¿Qué tipo de acción o reflexión te gustaría suscitar con tu escritura?

BB: Todo escritor quiere es que sus historias, relatos o ensayos realmente tengan impacto en la reflexión sobre estos temas, despertar un poco de esta especie de letargo impulsado por varios sectores, incluso por los grandes medios de comunicación y las redes sociales. El poder ha ido cambiando de lugar y, especialmente, nos dirige desde esos espacios donde todo el mundo está conectado.

Todo parece estarse volviendo realidad: cosas que antes eran pura ficción.

Creo que siempre ha sido la idea y el valor que tiene el arte: tratar de despertarnos un poco. Como diría Kafka, un libro tiene que ser el hacha que rompa el mar helado que tenemos dentro, algo que quiebre esta paz extraña. No escribo con ese proyecto en mente, pero obviamente está. Es algo que incluso a mí misma me sorprende cuando lo veo.

Everything happening now used to be fiction.

Every writer wants their stories to make people think and reflect about the things that they’re talking about, and maybe even wake people up. These things we’re seeing are motivated by various sectors and their social media, so power is changing hands.

Art has this role; it can wake us up. As Kafka would say, art is the axe that breaks the frozen sea within us, something that shatters this strange peace. I don’t think I actually mean to write this way. But then I read myself, and I’m really surprised that I see it too.

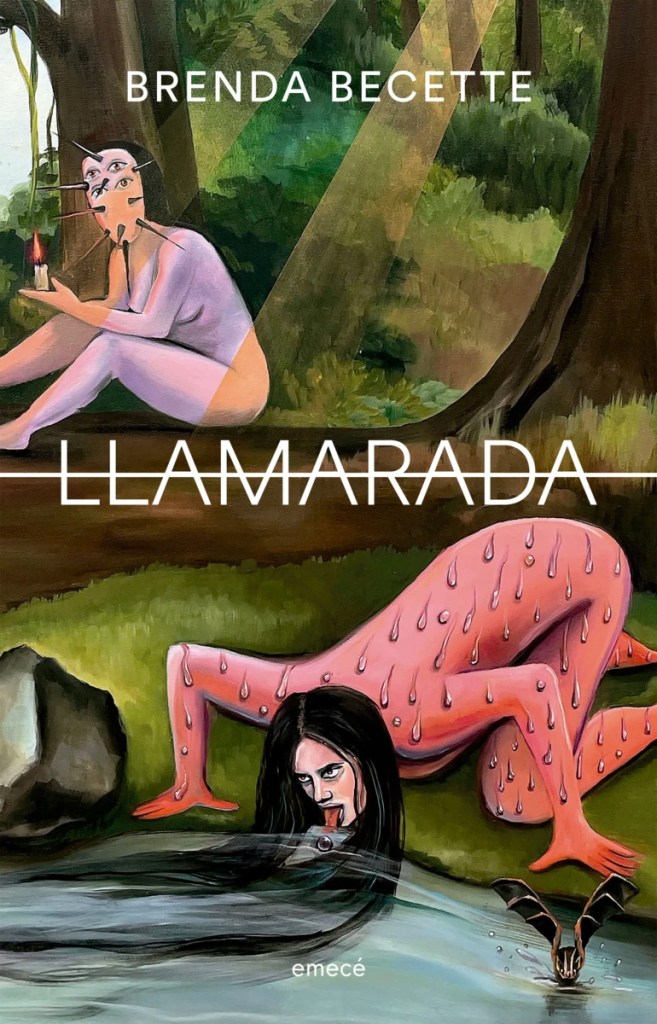

Featured image: Art from the cover of Llamarada (Emecé, 2024), Brenda Becette’s latest book.

Brenda Becette is a writer and clothing designer from the University of Buenos Aires. Her collection of short stories, La parte profunda (Editorial UDG, 2018), is the winner of the José Emilio Pacheco City and Nature Award at the Guadalajara International Book Fair in 2017. Two of her stories have been translated into English for the anthology Montañas, and three or four ríos (Editorial UDG, 2022). Her latest book is Llamarada (Emecé, 2024). Contact.

Bri Meyer is an anthropology Ph.D. and former Managing Editor of Edge Effects. She is now a research communications specialist for the UW–Madison College of Engineering, where she translates cutting-edge advancements for public or policy audiences. Catch her in nature, at a bakery, or at the gym. Contact.

Sally Perret is an Associate Professor of Spanish at Salisbury University. She has published in academic journals like the Hispanic Research Journal, the Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies, and Ínsula. Sally is also co-translator with José Bañuelos-Montes of two anthologies: Voces de la Resistencia/Voices of Resistance: A Bilingual Anthology of AfroColombian Women Poets (Editorial Ultramarina, 2021) and Poetryfighters (Editorial Ultramarina, 2022). She has been a participant of 4W-WIT since 2021. Contact.

You must be logged in to post a comment.