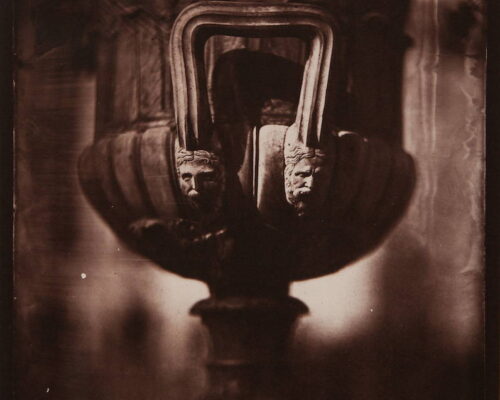

The Alchemy of Early Photography

The earliest photography offered a dazzling set of techniques to capture and reveal its subjects. During the nineteenth century, processes such as the tintype or daguerreotype were thought to illuminate the truths of the visible world by combining chemical knowledge with artistic insight. Today, these historical photographic techniques are being revisited in work that retrains the eye to see what lies overlooked, abandoned, or underfoot. In their own particular style, each of the four artists featured here uses forgotten processes to reveal objects and people that have been deemed disposable. Currently, their photographs appear together in an exhibit, Un/Seen: The Alchemy of Fixing Shadows. Un/Seen asks viewers to consider multiple iterations of historical methods, explore photography as science, art, and magic, and to reflect on what new ways of seeing might be produced in the process.

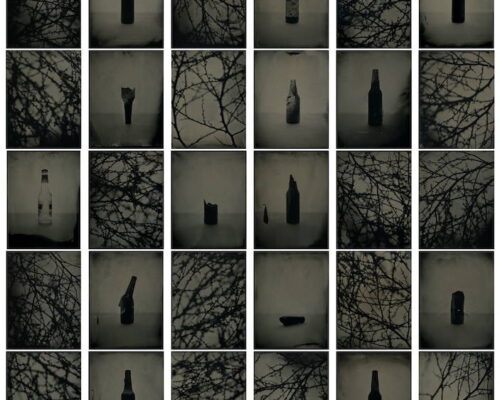

Jon Horvath, “Beer Bottles and Tumbleweeds (as Collected from the Hwy 30 Turnoff)”

Click to enlarge.

“All that remains in Bliss is two gas stations, a small school, a church, a diner, and two saloons to service its 300 current residents,” Jon Horvath writes of Bliss, Idaho, a formerly thriving railroad town along the Oregon Trail. The town is the subject of his ongoing transmedia narrative, This Is Bliss. The series includes object studies of scrunched dollar bills, tumbleweeds, and splintered beer bottles at the side of the road using the tintype: a wet plate process that develops a positive which cannot be reproduced. Although labor-intensive from a modern perspective, tintypes during the nineteenth century were often used to take snapshots of visitors at the seaside or fairground. Horvath’s tintypes of small-town debris evoke the ongoing association of photography with disposability. Like the snapshots of travelers passing through, there is an underlying sense that Bliss may soon be forgotten. And yet, for Horvath, Bliss remains worthy of granular scrutiny, down to a discarded beer bottle.

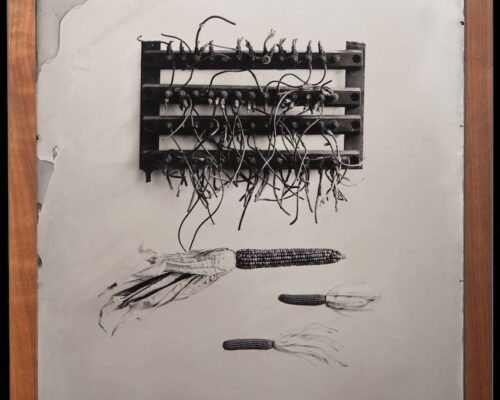

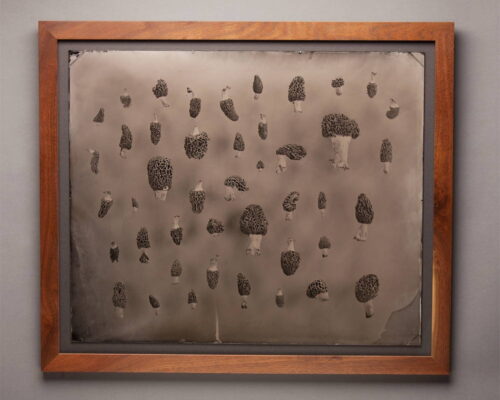

Tomiko Jones, Rattlesnake Lake

Click to view the full gallery.

Fragments of the natural world appear throughout the work of Tomiko Jones, who uses alternative processes as a strategy of revaluation. “I was feeling increasingly irritated walking up the road. Nothing about it was peaceful…it was garbage day,” she writes about The Squirrel, an elegy to the animal she found by the roadside. After she placed the corpse between two sheets of paper to make an imprint, Jones stepped back to decide where to place the final sheet and witnessed a dump truck squash the body. She then carried the squirrel home to create a cyanotype with the unrecognizable remains. Jones frequently combines on-site techniques with historic processes. For Rattlesnake Lake, she collected lake water to clean the film “as an invitation of the lake to merge physically into the image” and developed them using platinotype, which combines platinum and palladium exposed to ultraviolet light. Here, the lake becomes both the subject and physical part of the image, asking us to reevaluate the relationship between the darkroom and the natural world.

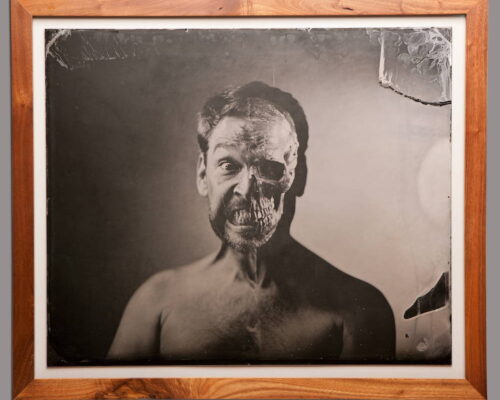

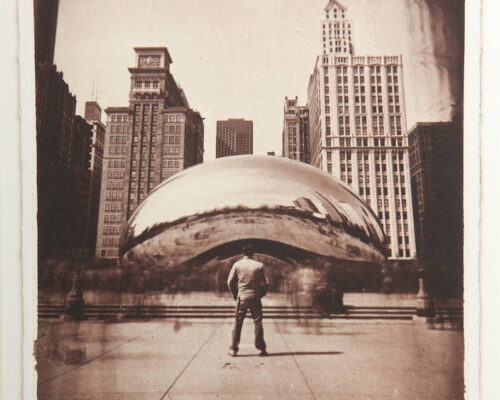

Eric Baillies

Click to view the full gallery.

For many of the artists in the exhibit, historical processes become opportunities to re-engage our familiar surroundings. Eric Baillies, for instance, uses techniques such as tintypes, carbon, and salt prints to spark a sense of wonder at, and care for, the familiar. His salt and albumen prints, each “coated by hand, contact printed in the sun, toned in gold chloride and signed and waxed,” often depict the nonhuman world: opium pods, a shrivelled gourd, a woven tree. The son of a chemist who recreated a nineteenth century natural light studio and who blogs as The Photo Chemist, Baillies also confronts the chemical reactions that make these scenes possible. In addition to his photography, he holds workshops and sittings to familiarize the public with historical processes.

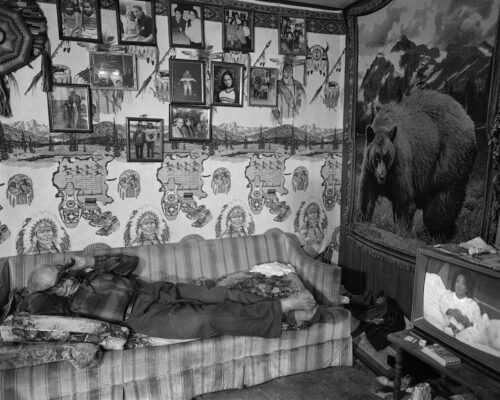

Tom Jones, Choka Watching Oprah

Click to enlarge.

More than the other artists in the exhibit, Tom Jones focuses on human subjects that have been too often treated as disposable. He celebrates Indigenous history and documents the contemporary lives of Ho Chunk and other Native American peoples using gelatin silver prints. “Mindful of [his] responsibility to the [Ho Chunk] tribe” and working “to carry on a sense of pride about who and what we are as a people,” Jones responds to historical photographs of Native communities that objectified and simplified the lives on view. Works such as Choka Watching Oprah portray the subject in a domestic space, surrounded by personal art and possessions that are far from tokenizing. Jones’s intimate portraits of Native peoples bring the living present to bear on a past that has been warped and obscured. By lingering on identities which have been deemed expendable, Jones encourages us to look differently at dominant histories.

Selections from these artists’ work will be on view as part of Un/Seen: The Alchemy of Fixing Shadows, which runs February 15 to April 14, 2019 at the Chazen Museum and showcases nineteenth century photographs alongside contemporary reworkings of traditional techniques.

Featured image: Tomiko Jones, The Squirrel, (2017).

Iseult Gillespie is a Ph.D student in the Department of English at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Her work focuses on experimental forms that lie at the confluence of theory, memoir, and performance. She is particularly interested in the relation of experimental aesthetics to critical theories of gender and sexuality, race, and disability, and in how these connections can illuminate alternative structures of relation, care, and refusal. She is a TED-Ed educator and a Mellon-Morgridge Graduate Fellow, and is committed to spaces that allow the relationship between scholarship and public interests to flourish. Contact.

Tori Yonker is a Ph.D. student in the Department of English at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Her work focuses on the haptic interplay between the sonic and the visual through the formal lens of comics studies. Tori is particularly committed to injecting the theoretical lenses of black feminist studies and Asian American studies into her readings of 20th-century American comics. Her firsthand experience in curatorship and studio arts allows for a combining of theory and praxis, an essential exercise for our contemporary moment. Her last contribution to Edge Effects was “Weathering this World With Comics.” Contact.