Visualizing the Volcanic Caribbean

Volcanoes are always in the background of life in the Caribbean.

— Matthew St. Ville Hunte, The Paris Review

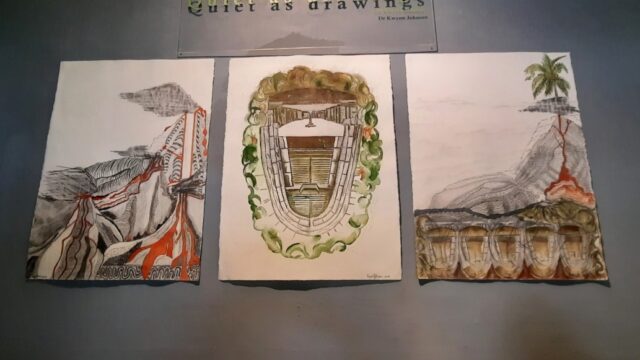

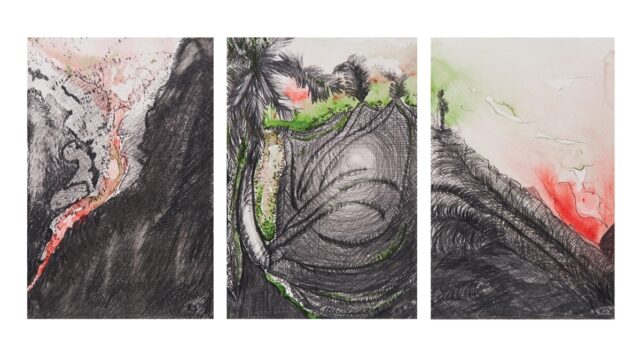

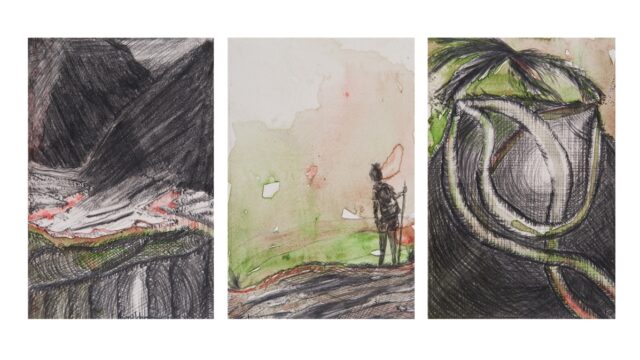

Quiet as drawings is the title of my 2021 art exhibition, a collection of 21 triptychs of graphite drawings and watercolor. This series drew from an encounter with the 2017 translation of the 1957 novel titled La Danse sur le volcan [Dance on the Volcano] by the Haitian author Marie Vieux-Chauvet. Set in the 1790s, the story centers on the Haitian opera singer Minette, and the volcano in the title represents the escalating brutalities and complexities of life leading up to the Haitian Revolution. These 21 triptychs re-present the physical volcano as affecting life and history in our twenty-first-century Caribbean archipelago—its foreboding, volcanic, eruptive, and explosive nature, and the possibilities of re-formation. These 63 drawings with watercolor do not attempt to conform to the logic of representation; instead, they seek to illuminate things below the surface and present new ways of looking at and knowing our lived landscapes. Quiet as drawings is a continuation of my visual work in Caribbean cultural geography.

In these graphite drawings, I use a limited palette of sap green and cadmium red and imagery that moves away from the superficial cliché of Caribbean landscape paintings. For the viewer, life in this palimpsest-like landscape is experienced through the two women figures who travel through all of the triptychs. (The male figure only appears in two of the 21 triptychs.) The two women animate the compositions as they traverse, pause, and experience a somewhat literal and symbolic volcano—before, during, and after an eruption. The viewer is left to decide what these two women are observing, exploring, and experiencing.

Though I’m engaging with a disaster hazard in the Caribbean, I seek to move beyond the fatalistic and toward the aspirational. The two women who travel through the triptychs are never presented in any immediate danger or fleeing from a scene. The viewer will have to decide if these triptychs present a landscape that is pre-apocalyptic or post-apocalyptic. Further, the underlying theme of disaster has global relevance that moves beyond the Caribbean landscape.

The Volcano as Symbol in Art History and Literature

Visual representations of volcanoes—part of the landscape genre—run through the history of art. For centuries, artists have drawn from this natural phenomenon to probe humanity in these sites of disaster. These works have also been an act of bearing witness via artistic testimony. There is a large body of work throughout art history that depicts disaster and explores the absurdity of life in the wake of disaster. Explosive volcanic eruptions offer artists a way to explore the drama of light, shadow, volume, tone, texture, and movement. An early example in the Caribbean is J.M.W. Turner’s well-known 1815 oil painting depicting the 1812 eruption of La Soufrière, which has informed areas such as literature, film, photography, geological enquiry, volcanology, and mythology.

These triptychs visually articulate an alternative way to consider the Caribbean of the twenty-first century.

Volcanoes and their explosions as symbol have also appeared in many works in Caribbean literature and poetry. Trinidadian scholar C.L.R. James uses the volcano in his 1938 preface to The Black Jacobins as a metaphor to analyze the notion of the suddenness of revolutions and, more importantly, what causes revolutions. James posits that we must excavate the symbolic “sub-soil” that gave birth to an eruption in Saint-Domingue, now Haiti, in the late eighteenth century. In considering this idea, the triptychs in Quiet as drawings depict a quiet yet foreboding landscape. Below the topography, there is a stylization of geological formations, earth stratification, and outcrops. In this way, the creative imagination as a way of knowing presents a visual language to articulate both life and the subterranean composition—its shifts and rhythms, what later surfaces and resettles.

These 21 triptychs can be located within the broader art-historical timeline that includes visual and written works that have explored volcanoes. For instance, the eruption of Italy’s Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE can be found in early literary documents by Roman magistrate Pliny the Younger. Vesuvius has also inspired later works including Clarkson Frederick Stanfield’s 1839 An Eruption of Mount Vesuvius housed in the Tate’s permanent collection, a 1985 screen print by American pop artist Andy Warhol, and Susan Sontag’s 1992 novel The Volcano Lover, whose book cover features the 1799 Vesuvius eruption rendered by eighteenth-century Italian painter Pietro Fabris. This art history includes depictions of other volcanoes, including Indonesia’s Krakatoa volcano; Chile’s most active volcano, Villarrica; Mount Fuji on the island of Honshu in Japan; Mount Cameroon near the Gulf of Guinea; and the Nyamuragira volcano in the Democratic Republic of Congo. For centuries, and around the globe, volcanoes have inspired artistic inquiry and expression.

The Volcanic Caribbean

Here in the Caribbean, while La Soufrière in Saint Vincent was erupting in 1902, so too was Mont Pelée in Martinique. The Dominican author Jean Rhys would later publish the short story “Heat” in 1976, drawn from her memory as an eleven-year-old girl witnessing ash falling on the streets of Roseau from the eruption of Mont Pelée. In 1947, Aimé Césaire in his epic poem Cahier d’un retour au pays natal [Notebook of a Return to the Native Land] used Mont Pelée’s explosive eruption as a symbol to critique the French department of Martinique. He opens by describing how Martinican society in 1947 was similar to that of 1902—“indocile to its fate,” filled with “fears adrift in the sky, . . . piled up fears and their fumaroles of anguish.” By the end of the poem, however, the “shackled volcanoes” evolve into possibilities for transformation.

The volcano as a symbol for renewal can also be found in works by the Barbadian poet and thinker Kamau Brathwaite. He explored the geological formation of the Caribbean archipelago—how the subduction zones created from shifting tectonic plates formed our islands and the volcanoes that dot the archipelago, “a geological plate being crushed by the pacific’s curve . . . / the history reflects the pressure and passage of lava.” Brathwaite notes how art as a way of knowing enables us to understand the present through the lens of the past. This past involves the formation of our archipelago, its ongoing remaking, and most importantly, the possibilities of unexpected and newer transformations.

How do these images explore volcanoes as both a geological feature and as a disaster hazard?

Reports of the 1902 eruption of La Soufrière remind us how disaster shapes the socioeconomic conditions of the working class. The later eruption of La Soufrière in 1979 led the Vincentian musician and poet Ellsworth McGranahan “Shake” Keane to create The Volcano Suite. Keane’s poetry critiques the neglect of the working class and their lived realities and reveals how class structures remain in place during and after a disaster.

I continue this tradition of examining the cultural significance of volcanoes with my own artistic intervention, Quiet as drawings. The exhibit ran from March 1 to March 22, 2021 at Soft Box Art Gallery in Port of Spain, Trinidad. After 42 years of quiet, La Soufrière had an explosive eruption shortly after the exhibit ended, on April 9, 2021. As Jean Rhys describes the 1902 eruption in “Heat,” the ashes of the 2021 eruption reached and blanketed other neighboring islands. In many ways, its ashes cover my work too.

Quiet as drawings

The volcano, which for long years the planters did not believe existed, was erupting. Like lava and ashes, the slaves poured from the hills, left the workhouses and the forests as if vomited up from a crater.

— Marie Vieux-Chauvet, Dance on the Volcano

Quiet as drawings is set against this backdrop of volcanic eruption. The exhibit draws on Vieux-Chauvet’s and James’s use of the volcano as a metaphor to explore the inevitable eruptions. Quiet as drawings is a continuation of my visual analysis of place and meaning, using the creative imagination to explore contemporary life in landscape, specific to Caribbean cultural geography. This essay is not meant to prescribe what this work means. Instead, I ask the viewer: what, through the unique capacities of visual language, do these 21 triptychs make you begin to think about? I suggest that we move away from asking “What does it mean?” and ask instead, “What is it doing?” and “How does it work?” How do these images explore volcanoes as both a geological feature and as a disaster hazard in the twenty-first century Caribbean?

The one prescriptive cue I have offered to the viewer is the title of the exhibition. “Quiet as drawings” comes from a phrase in Derek Walcott’s illustrated book-length poem Tiepolo’s Hound. Walcott uses this expression to powerfully and simply describe characters strolling along a street. This descriptor of how a drawing works, rather than what a drawing is, offers a framework for the viewer to contemplate both the technique of drawing and volcanoes. As an artist making work for a general audience, drawing as a medium is one that has to rub against new media, and a volcano is something that one might, if ever, only witness once in a lifetime.

In thinking through the thematic elements, and the formal, technical, and material properties in this work, alongside my own reflections on Caribbean cultural geography, Quiet as drawings speaks to both the physical and the metaphysical. These 21 triptychs involve an interdisciplinary approach and triangulated perspectives to visually articulate an alternative way to consider the Caribbean of the twenty-first century. The creative imagination as a way of knowing thereby emerges as Quiet as drawings.

These drawings seek to illuminate things below the surface and present new ways of looking at and knowing our lived landscapes.

While creating this work from 2017 to 2020, I was inspired by Vieux-Chauvet’s Dance on the Volcano, set during the Haitian Revolution. As the exhibition closed, we witnessed the latest explosive eruption of La Soufrière and the reception of this work went on to figure differently. However, I hope that viewers might consider how disaster is often a slow burn, which can often lead to indifference, as we are seeing with the current pandemic. Disaster is also easily normalized—consider crises in Haiti and Afghanistan, catastrophes wrought by capitalism, and the exploitation of workers, especially Black working-class women. Moreover, as there are numerous sites of disaster erupting around the globe, there are others that are too brutal to speak about and do not make it into the news or social media. Disaster affects everyone differently. In Dance on the Volcano, the protagonist Minette grows into her revolutionary consciousness, while her sister Lise succumbs to capitalism and slavery. In these volcano drawings, I seek to give expression to all these concerns and all that cannot be said.

Featured image: Volcano Triptych 5/21 from Quiet as drawings, 2021. Each of the three panels make up a triptych and measure 22.5 x 15 cm. Watercolor and graphite on 140-lb cold-pressed paper.

Dr. Kwynn Johnson is a visual artist and a scholar of Haitian studies and cultural studies. Since 2003, Johnson has had nine solo art exhibitions. She has also exhibited in several local, regional, and international group shows in Haiti, Guadeloupe, New York, and in spaces such as the Tate Modern in London, several Haitian Studies Association Conferences, and four editions of the Ghetto Biennale in Port-au-Prince. Her last contribution to Edge Effects was “Excavating Haitian Histories” (May 2019). Twitter. Contact.