At the Confluence of Art and Science

Can artists and scientists cross seemingly rigid boundaries to work together?

In 2014, two professors at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Laurie Beth Clark from the Department of Art and Steve Carpenter from the Center for Limnology, received funding for an interdisciplinary project to bring artists and scientists together to think about long-term ecological change. They asked two artists, Jojin Van Winkle and Helen J. Bullard, to find two scientists with whom they wanted to work. The professors also sought out a qualitative social scientist, Sigrid Peterson, to study the process of art-science collaboration.

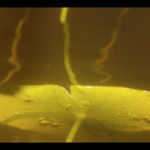

Two years later, our projects are deep in production. Filmmaker Jojin Van Winkle and aquatic ecologist Alison Mikulyuk are working on a series of films, photos, and scientific data describing the Namekagon River in Northwest Wisconsin, one of the first national wild and scenic rivers. The resulting project, “Voices of the Namekagon,” will eventually be hosted online through a map-based website.

Research-based storyteller Helen J. Bullard and ecologist Chelsey Blanke are busy creating a collection of stories—told through voice, music, video animation, and images—to share fragments of the cultural, ecological, and industrial histories of Lake Michigan, the only Great Lake to sit entirely within the borders of the United States. “Restless: Stories from Lake Michigan” will be distributed through multiform live performances, presentations, and short films incorporating montage and animation. Parts will also be housed online.

Sigrid Peterson, a human geographer and qualitative researcher, is processing ethnographic data on art-science collaboration as an expression of interdisciplinarity in academic scholarship. She will report her work in several forms, including a comic zine.

At the outset, we shared the concern that, too often, art-science collaborations become an artist tasked with the public communication of scientific findings, or a scientist dabbling in art. We wished to avoid this and instead place equal importance on artistic and scientific approaches to research. Yet we consistently confronted questions rooted in disciplinary language (e.g., Where is the “science” in this project? What does the “art” achieve from a research perspective?). We were enthusiastic about generating a different discussion: not, “is this art or science?” but, rather, “can this work have its own identity and agency?”

Apart from the charge the professors gave us to “have a life-changing experience,” there were few specific instructions or parameters to guide our collaboration. Consequently, our pairings employed very different processes. Helen and Chelsey quickly discovered a shared interest in Lake Michigan, commencing field and archival work immediately—visiting libraries and museums and traveling along the Lake Michigan coast in order to gather stories, documents, visual materials, and histories. They found an open-ended, organic workflow that integrated personal interests and research elements from both of their practices.

Meanwhile, Alison and Jojin struggled at first to find common ground. In search of a mutual interest, they employed methods often used by qualitative researchers. At first, they cast a wide net, conducting in-depth interviews with a diverse group of ecological professionals, followed by the coding and analysis of that information. Eventually, historical footage of Gaylord Nelson led them to the Namekagon River. Then they too settled on an open-ended approach to the project, building relationships in the watershed that ultimately guided their work.

Throughout this process, Sigrid studied both teams to gain insights into the process of working across scholarly disciplines. She observed not only each project’s content and methodologies, but also the ways in which the two teams talked about their projects.

In our work together, we routinely conveyed a commitment to transcend rigid and sometimes mischaracterized disciplinary identities. We self-consciously tried to conceive and execute projects wherein neither collaborator’s medium, typical research subject, or disciplinary practice overshadowed the other’s. We adopted an egalitarian approach to question development and data collection, and we regularly reflected upon our relationship to the ecological and social communities of our studies, to one another as colleagues and friends, and to the type of “product” we would produce.

Both ecologists conveyed that collaborating with artists helped them view scientific practice from a broader perspective, provoking a consideration of their research writ large, and a new examination of the nature of the questions they ask as scientists. The two artists echoed a shift in how they reflect on their artistic practice. While their media and basic methods remained unchanged, both found the ways they question the world expanded with greater exposure to lab-science culture, ecological field work, and the process of scientific knowledge production.

We share the sentiment that the outcomes of our work extend well beyond our artistic-scientific pieces on exhibition. This opportunity not only asked us to produce collaborative knowledge. It also provoked us to engage in an ongoing metanarrative of what collaboration means for that production. During our recent presentation and panel discussion at the 2016 Performance Studies International conference in Melbourne, Australia, “Performance Climates,” audience members commented that this work is much more than the sum of its (traditionally exhibitable) parts, and that the ongoing productive dialogue it generates about why artists and scientists should collaborate is one of its more remarkable features.

The gallery that follows features selected images from these collaborations that will be shared as part of a performance, presentation, and conversation from 5-7 p.m. on October 5, 2016 at the UW-Madison Discovery Building‘s DeLuca Forum. Enjoy!

Featured Image: Chelsey Blanke (L) and Helen J. Bullard (R), contemplating Lake Michigan, Rock Island. Photo by Scott Larson, 2015.

Alison Mikulyuk is an aquatic ecologist working at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. Her research centers on understanding freshwater communities and the human activities that affect them. Contact.

Helen J. Bullard is a research-based storyteller, currently completing a special committee Ph.D. in Interdisciplinary Arts & Science at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, focused on the horseshoe crab. Contact.

Sigrid Peterson is a graduate student in the Departments of Journalism & Mass Communication and Library & Information Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She also has an M.S. in Human Geography with subject expertise in feminist economic geographies, the social scientific study of interdisciplinarity, and the restructuring of public higher education. She loves images and text, especially together, and drawing cartoons. Contact.

Jojin Van Winkle is a filmmaker and visual artist. Her pseudo-documentary films focus on resilience. Her documentary work centers on land and human rights. She has her M.F.A. and M.A. from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and is currently an associate producer for the documentary, The Land Beneath Our Feet. Contact.

Chelsey Blanke recently earned her M.S. in Freshwater and Marine Science at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Center for Limnology and now works as a Research Specialist at the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. Contact.

This research was supported with funding from the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation (WARF) through a grant provided by the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and Graduate Education aiming to foster interdisciplinary research. Additional support was provided by the UW Center for Limnology, Department of Art, Department of Zoology, Center for Culture, History and Environment (CHE), and the Robert F. & Jean E. Holtz Center for Science & Technology Studies.